One of the human impulses that’s most destructive to long-term investment success is the desire to maximize returns regardless of the risk in doing so. Whether this manifests in buying the popular stock of the day hoping for similar results in the future or buying a seemingly more diversified stock market index after a historically stellar run, the allure of good returns can distract us from what matters most – avoiding large losses. Although investing in “the market” via an index fund may not feel like it, at the wrong point in time it can be akin to swinging for the fences, just like with the hot individual stock. This isn’t to say that as investors we can’t take reasonable swings when we have a pitch down the middle, nor is it to say that losses can always be avoided. The point is that the majority of the time, when the ideal situation doesn’t exist, we should seek out little victories – opportunities to advance the runners, one base at a time, one runner at a time. We can almost look at retirement planning or maintaining financial independence as starting a baseball game with a three to nothing deficit. Assuming we hold the opposing team to three runs, we have nine innings to get four. If we take too many chances at inopportune times, we’ll fall short. If we focus on probabilities and pick our spots, we have a very good chance of getting the win.

A good example of this is the last 16 months, since financial markets started turning south. Over that period of time, the S&P 500 is down ~-10%, the Russell 2000 (small caps) ~-20%, high grade corporate bonds ~-11%, and long dated U.S. government bonds ~-24%. So much for traditional stock/bond diversification, eh? Now, let’s say that rather than being down ~-12% in a diversified portfolio over the last 16 months, you broke even. Although you didn’t gain anything, you also, and in this environment more importantly, didn’t lose anything. What we know about human nature is that this wouldn’t feel like anything special until it’s put into perspective and measured against what most other investors experienced, after which it probably still wouldn’t feel that special, because we’re human. But although it may not feel special, it should be viewed as a little victory. How important are these little victories, you ask? Very important, assuming they occur as the result of an investment process that is repeatable.

Loss Minimization Focus

Let’s assume that we’re in a market environment that is late-stage and overdue for a rough stretch, which we would debate all comers that we are in fact in. In the chart below, under “Portfolio A”, we have a ten-year sequence of returns with a numerical average of 3.5%. Based on today’s valuations and growth prospects, we would do very well to achieve this average over the next 10 years, if not much longer. For simplicity, we repeat this pattern over thirty years. In the second column labeled “Portfolio B”, we have the same returns with the exception of the three negative years, where we do 10% “less badly”. This increases our numerical average return to 6.5% from 3.5%. The question of course is, what would the impact of the little victories in the latter return sequence repeating over a 30-year period be on one’s retirement plan?

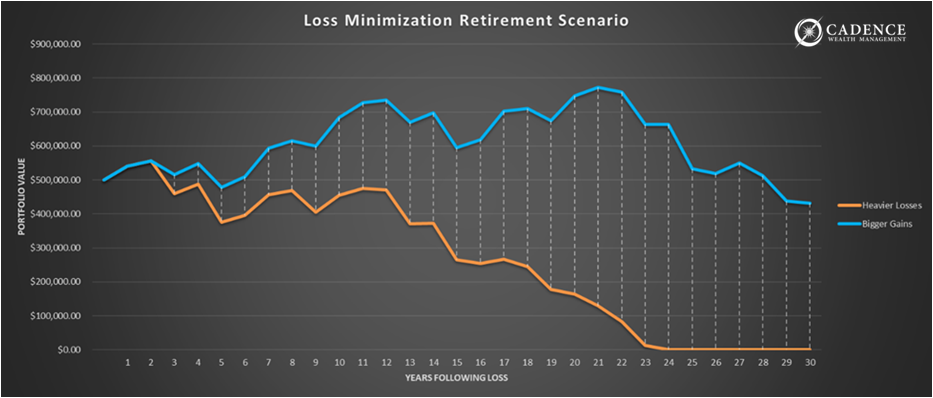

To find out, we first have to think of a hypothetical investor scenario. Let’s assume we have a retiree or retired couple that is bringing in $40,000 of fixed income annually, spends $50,000, and has a portfolio of $500,000. So, there is an income shortage of $10,000 per year that the portfolio has to provide for. Let’s also assume that the expenses grow at 4% each year and the fixed income at 2%, which approximates social security income growing at half the rate of price inflation (cost of living). For simplicity, let’s also assume that any taxes owed are built into the $50,000 expense figure and our investment process achieves the same returns in all years except for those three bad years in the sequence, where we lose less. It’s worth highlighting that we’re not suggesting this is likely or easy to accomplish. We’re merely keeping this exercise simple to illustrate the importance of minimizing losses in bad market environments. Okay, with all that laid out, let’s look at the black chart below.

What you’ll notice is that by minimizing losses in 9 bad years over a thirty-year period of time, one goes from running out of money in year 23 to having more than $400,000 left in their nest egg at the end of our retirement timeframe. This is, shall we say, kind of a big deal. In any one of these nine years where losing less may not feel like anything special, over time, and in the grand scheme of things, it’s a critical part of a successful investment result and retirement plan.

Big Swings Focus

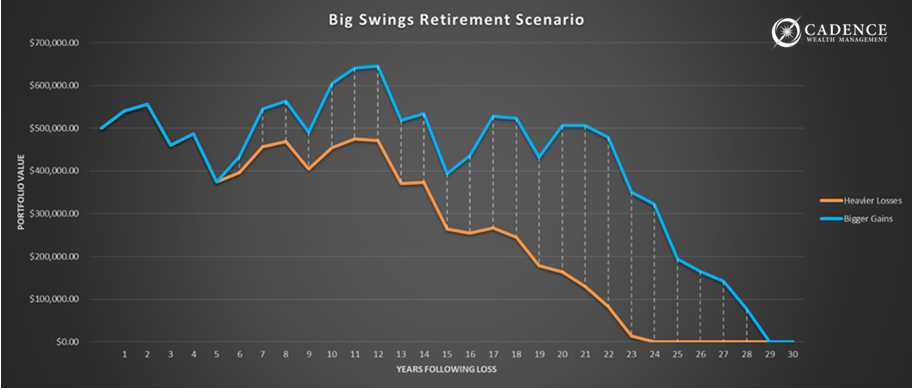

Now, let’s say that rather than committing to an investment plan that prioritizes loss minimization, we focus instead on taking big swings and trying to maximize returns in the good years. In the matrix below, you’ll notice our returns in “Portfolio A” are the same as before, but in “Portfolio B”, rather than losing less in the bad years, we increase our returns in the three best years by 10% each year. The end result is a bump in the average numerical return from 3.5% to the same 6.5% we saw in the loss minimization example. The strange thing, however, is that rather than our hypothetical retiree(s) ending up in the same place at the end of thirty years, they are much worse off, running out of money around year 29 (see black chart below).

The reason for this is purely mathematical. If we have a two-year sequence of returns of -50% and +50%, the quick numerical average of 0% tells us we should end up right where we started, only that’s not how it works. Starting with $100, we drop to $50, then back up to $75 after the second year. Reverse the order and we get the same thing; up to $150, then down to $75. Although the order doesn’t matter in this example, it does come into play when we’re adding and withdrawing from the portfolio. That’s a topic for another day, however. The point here is that losses matter more to investment success than gains – way more. Looked at another way, the S&P 500 is about 175% higher than it was at its peak in 2007, 16 years ago, but it would only take a -65% loss to wipe out all those gains. Impossible? Unfortunately, it’s not. Every stock market bubble over the last 100 years has come down at least -50% with a few -80% plus declines thrown in there for good measure (Dow 1929, Nikkei 1989, and Nasdaq 2000). Decades of progress can be lost in months and years. Losses simply matter more. Although this example may sound pessimistic to some, what I’ll confess is this; sometimes an honest, informed assessment of things isn’t so rosy. Viewing a not so rosy situation objectively does not make one pessimistic. Pessimism is a frame of mind. We can either ignore reality or focus on doing something about it in a constructive, productive way. Our plan, given the current reality of the situation, is to focus on asset classes that make good investment sense and minimize losses to the best of our ability.

So, if you’ve managed to break even over the last 16 months because you’re managing risk and doing it differently than most, congratulations. Most of our clients know what we’re talking about here. Although it may not feel like progress, it absolutely is. In avoiding larger market losses, you’ve advanced the runner and scored a little victory, and it’s these little victories accumulated over time that get you the win. One hit at a time, one runner at a time. It’s been a great 16 months and a great start to 2023.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May 2023 edition of our “Cadence Clips” newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.