Speculative manias are incredibly difficult to navigate without injury. For every millionaire produced by the technology bubble of the late 1990’s, there are countless stories of people losing their life savings or worse. Fast-moving markets that are well beyond any reasonable assessment of fair value can reverse course without warning, reason, or sympathy for the investors who don’t have the good fortune to exit the game before the music stops. This is the problem with speculation: because, like moths to a flame, we’re attracted to those assets that are rapidly going up in price and garnering enthusiastic praise, there is usually no emotionally sound reason to get out of them before they drop in price significantly. With the major U.S. stock indexes back to all-time highs, it’s more important than ever that we’re aware of the risks and rewards of chasing fast-moving performance. These are the market periods throughout history where the biggest and most consequential mistakes are made, mainly because it’s in our wiring to make them. Few would disagree that the default human impulse is to seek safety in the herd, go with the flow, take short-cuts when it’s easy to do so, etc.; all characteristics that tug on us in these types of stock market environments. I think most would be fibbing if they said there wasn’t at least an occasional voice in their heads asking them to dump everything into Nvidia, tech stocks, or Bitcoin. Whether we listen depends on us knowing ourselves, who we are – an investor or a speculator.

There are two ways to think about figuring this out that might be helpful. They are the two general approaches to investing.

Buy High, Sell Higher – The Speculator

This approach describes the speculator, or anyone buying most tech stocks today. There is little regard for the current price so long as it continues going up long enough to sell at a profit. As I mentioned above, for the emotional reasons often wrapped up in this approach, the selling usually doesn’t take place until after a large drop in price at some point in the future. You may be wondering; “What if I have rules in place to sell before that big drop happens?” As we discussed in our December 2023 edition of Clips, having disciplined exit rules around speculative markets is much harder than it sounds. Selling too early makes for inadequate reward for the risk we’re taking, while selling too late leaves us vulnerable to large and sudden losses. It’s also worth noting that selling too early often leaves speculators out of the game long before the rise is over, which in this current market means they would have sold plenty of speculative assets back in 2017, as an example. Of course, being a speculator, the urge to chase hasn’t gone away just because this person sold out at a small profit, and so the dilemma continues. A person adopting this technique tends to continue buying expensive assets until they fall dramatically in price.

With that in mind, here’s some math. Say, for example, we invest in a fast-moving shiny thing that goes up by 30% only to subsequently drop by 30%. If we start with $100, we get up to $130 before that 30% decline takes us back through what we started with to $91. Again, since the reason for chasing this hot investment was more emotional than fundamental, almost all speculators end up holding until the music stops. It’s also extremely common to hold the falling asset much longer than one should because of the strong desire to get back to break-even. It’s not unusual for speculative investments to eventually drop in price by 80%, and not at all uncommon for speculators to hold them all the way down. The bottom line, as history so robustly informs us, is that chasing returns in speculative manias for most is akin to a light-hearted game of Russian Roulette with a gun we’re convinced isn’t loaded because it hasn’t gone “bang” yet. Every speculative mania comes with bullets and the risk of severe, lasting loss. For most, the potential loss is just too great to justify the reward.

Buy Low, Sell High – The Investor

Similar to the buy high, sell higher approach, this one’s very difficult to implement effectively, but for completely different reasons. Whereas chasing returns higher is easy to do emotionally and extremely hard to make lasting money with over time, buying low and selling high can be hard to implement emotionally because it often requires buying investments that are out of favor. Investments that are out of favor aren’t discussed very much, which means we don’t get that validation from others that we seek as humans. Buying low often means we buy something that hasn’t gone up a lot (yet), isn’t overly popular, and thus leaves us feeling relatively unsure. As the low-priced investment starts working and garners more and more attention from others, it becomes easier, especially as other more popular investments start failing and reversing course. Validation. Eventually we arrive at the selling part of this approach where the investment has gone up in price so much that it’s morphing from an investment into a speculation. That’s the point where selling needs to happen and capital redeployed into better investments as gains can be wiped away quickly once in this speculative category. Over long periods of time, buying an investment low is a much safer and more surefire way of making money than buying a speculation high and hoping it will go higher.

Where Are We Now?

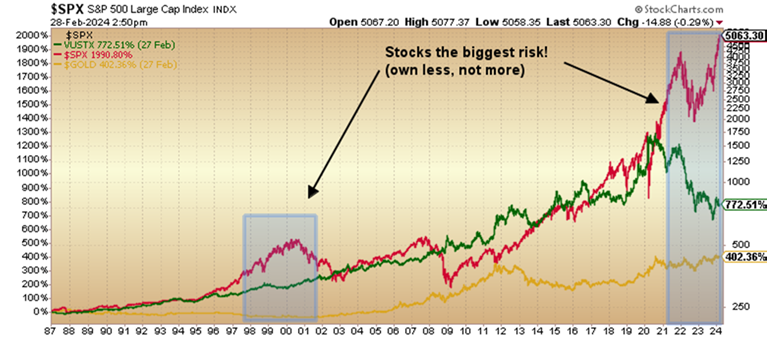

A glimpse at the chart on the following page will give us little doubt as to how extreme the situation is today. The red line is the S&P 500, the green a U.S. Treasury Bond fund, and the yellow, gold. These three major asset classes going back to 1987 have all had separate periods of good and bad performance with stocks up the most since then. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that just because stocks have won over this timeframe, they don’t always come out ahead over all 38-year stretches. Investors tend to think that because stocks are “riskier” they are certain to generate higher returns over time. This isn’t always the case, and there’s no rule that says it has to be. Stocks, being higher on a company’s capital stack, promise the opportunity for higher returns if all goes well.

If the company fails, however, stockholders are the first to lose their money while bondholders are the last. So, although stocks can and often do return more than bonds and gold over long periods of time, they don’t always. This is quite literally the definition of risk. The more of it one takes, the greater the chance of a bad outcome. Just like any other investment, stocks make the most sense when the current price implies a future gain that compensates us for the risk. The idea of stocks always making investment sense is ridiculous, just as it is for any other asset category. The price and value of an asset and resulting risk/return characteristics should be the driving factor in selecting assets for an investment portfolio.

Those times when stocks underperform bonds and gold for long periods almost always follow speculative manias – points in time where prices get far too high given underlying revenues, profits, and other economic fundamentals. Below, we can see the ramp up in the stock market in the late 90’s and again beginning around 2017. If one is operating as an investor rather than a speculator and aiming to buy something low, they would be buying treasury bonds and gold (as well as other commodities) today and shunning the runaway stock market. Had they done that in the late 90’s prior to the stock market bubble popping, they would have avoided 13 years of zero performance from stocks between 2000 and 2013, and instead 13 years of very strong performance. The same would have been true in the 1929 bubble leading up to the Great Depression, and to some extent with commodities in the late 1960’s. These were both periods where the stock market suffered negative returns for more than 10 years. Stock valuations, by most metrics, are higher today than at the height of those prior market bubbles – 1929, 1968, and 2000. There is no reason to expect we won’t see a similar resolution to this one when the euphoria wanes.

When it comes to owning long-term bonds, the vast majority of the return one gets is based on the prevailing interest rates at the time most of the bonds were purchased. So, if we assume that twenty years ago, one bought a portfolio of twenty-year treasury bonds and held them, they would have expected a return of over 7%, which is exactly what they got into 2021. The green line in the chart above shows that trajectory over time. Since long-term rates are back over 4%, an investor in bonds today could expect roughly that return over the next ten to twenty years with some fluctuation along the way. The important question for someone considering owning bonds now is, “Does a 4% return in long-term bonds seem more attractive than what I’d likely get in stocks over a similar timeframe?” At current stock market valuations, in looking at a number of different metrics, our opinion is that the answer to this question is “yes”. With current broad stock market valuations roughly 150% above historical averages, the next 10-20 years are likely to be a very volatile trip to nowhere. The 4% from long-term bonds is a good deal higher than 0%.

Gold (and other commodities), the yellow line on the chart on the previous page, probably offers even more potential. When we look at valuations of companies operating in the natural resources sector as well as commodities themselves, valuations are the mirror image (opposite) of those of the broad stock market, and tech stocks in particular. Because they have been neglected for the last 10 -12 years, valuations are near historical lows. Investment potential for this category of assets has almost never been better. So, to sum up our order of preference for the big three we’re talking about here, natural resource stocks and commodities offer tremendous long-term value, high quality bonds offer a little, and tech stocks and the major U.S. stock market indexes offer mostly risk and very little long-term value.

So how do we make sense of these stressful markets today? As hard as it can be to execute, the answer is pretty simple. We decide whether we want to be investors or speculators. If we choose the former, then we need to be willing and able to ignore what’s happening in the casino. If a few of the speculators are fortunate enough to walk out with a bunch of new found wealth, good for them. Most won’t. We also need to be willing to accept fluctuations that come from owning good investments and not take them as a sign that we’ve chosen poorly. This can be harder to do when the alternatives are behaving better. We tend to compare. We shouldn’t. It’s apples and oranges. Everything worth owning fluctuates in value and that fluctuation doesn’t mean that a good investment suddenly becomes speculative. When investing gets difficult, which it is guaranteed to do at points, it’s usually best to step back, reassess why we’re doing what we are, and whether something’s changed in the landscape that warrants a change in our plan. If not, as investors, we turn off the television, quiet the noise, and focus on things that matter more. Investors will be fine in the end. Speculators almost certainly will not be. It’s important that we know which one we are.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March 2024 edition of our “Cadence Clips” newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.