John Pierpont Morgan was known to have said, “Nothing so undermines your financial judgement as the sight of your neighbor getting rich.” Understanding the bigger picture can help us avoid unrealistic performance extrapolation (both up and down) and stay focused on those things that truly offer the most opportunity for lasting gain. There’s no more important time than now to look forward rather than backward.

This year has been particularly dangerous, not because markets have imploded, but because the way they are moving exposes our psychological vulnerabilities as investors. After a strong 2017, U.S. stocks ran up very aggressively in January, leaving those invested in them validated and further emboldened and those who weren’t envious and discouraged. As a result, more money from both groups poured into U.S. stocks in January – just in time to crash 10% over the first week of February. Since then, the question in investors’ minds has been, was that an isolated event or the beginning of a larger decline? With some indexes above the January 26 market peak and others still below it, the answer to that question still remains elusive.

While U.S. stocks have rallied off their February lows, other asset classes have struggled. Herein lies the danger. Those investors who favored U.S. stocks prior to the scare in February have been rewarded for not deviating. Those who were skeptical or more conservative? Well, those investors are back to feeling left out, envious, and doubtful about the efficacy of their approach, just as they did prior to February. The fact that most other investment categories have struggled this year (as discussed in the other piece this month) makes these emotions even stronger. These are the times when the most dangerous and impactful investment mistakes are made; right here. That intersection where greed from gains meets fear of missing out, two previously different groups of people coming together, is one typically found at crucial pivot points. Investors tend to extrapolate when they shouldn’t. Meaning, they assume the performance, good or bad, that has happened recently will continue into the future.

Markets aren’t conducive to extrapolation – they go up and down. For the long-term investor, generally the best time to buy something is after it’s gone down significantly while the best time to sell is after it’s gone up. Buy low, sell high, right? Extrapolation would cause one to do the exact opposite – sell that which has gone down thinking that it will continue to and buy that which has gone up convincingly, expecting more of the same. Over the short term, sure. But longer-term, this extrapolation led by hindsight bias can sabotage us as investors, yet that’s what our brains compel us to do if left unchecked.

The last twenty years alone is littered with examples of how this extrapolation can get us into trouble. Here are a few…

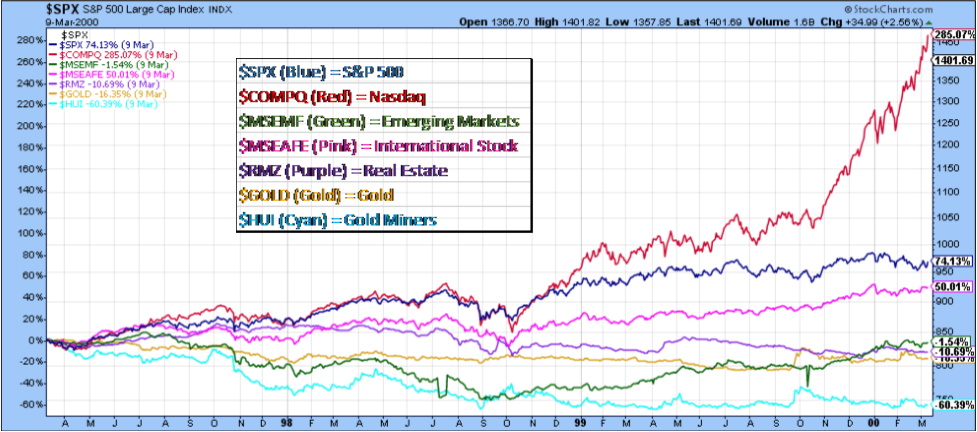

- Nasdaq in the late 1990’s – It was leaving every other asset class in its wake up until early 2000. By then, those invested in tech stocks were convinced it was the fastest way to riches and many of those who didn’t believe were converted along the way. Unfortunately, these 20%+ gains into perpetuity were not to be as the Nasdaq lost -83% of its value through 2002.

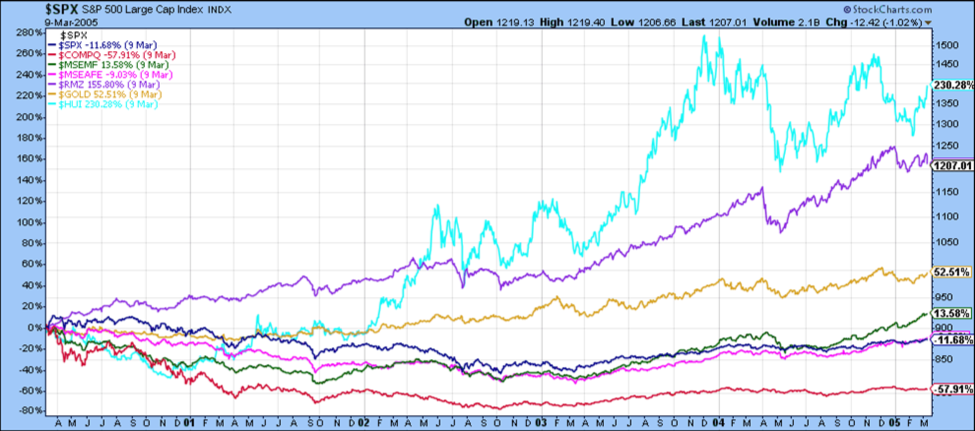

- Real estate through the mid 2000’s – With stocks down steeply through 2002, real estate was gaining favor as an asset class that could pick up the baton and get investors back on track. Real estate values held up very well through the bear market in stocks and by mid-2006, the MSCI U.S. REIT Index was up over 200% since things got ugly with stocks in 2000. If these gains continued at that rate, investors would make up any losses they had incurred prior in short time – only that’s not how markets work. Real estate as measured by the same REIT index went on to lose nearly -70% of its value from the middle of 2006 to March 2009.

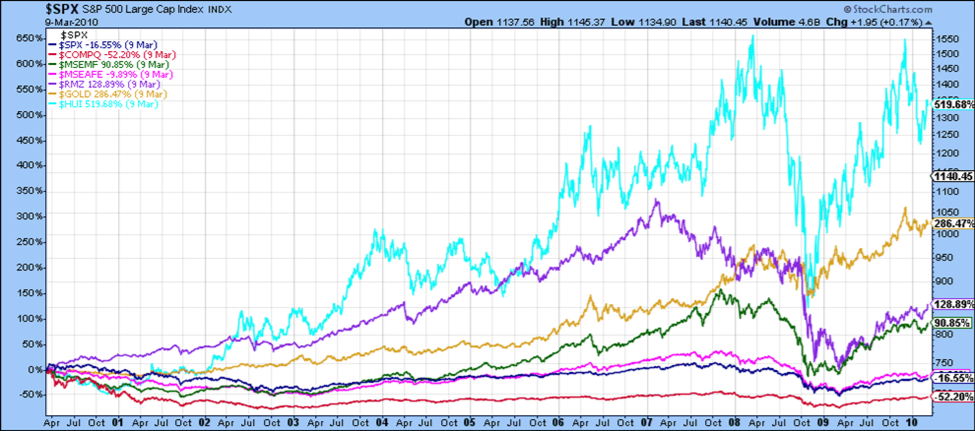

- Emerging market stocks – From late 2002 through late 2007, emerging market stocks enjoyed dominating performance over every other major asset class. The MSCI Emerging Markets Free Index was up over 400% at one point. These gains were virtually unprecedented and marked one of the largest stock bubbles in history. Extrapolation would have led investors to make all sorts of irresponsible decisions; invest everything in emerging markets, use leverage to do it, make large purchases with the confidence that money could be made back easily, retire early, etc. As with other top performing asset classes before it, emerging markets found their limits. Since October 2007, the MSCI Emerging Markets Free Index is down over -20%. That’s more than 10 years of losses for those who jumped on that bandwagon late.

- Gold through late 2011 – Similar to real estate, gold was a top performer through the tech bubble, and continued to do well prior to the financial crisis in 2008. However, when real estate and stocks fell substantially into 2009, gold held its value well and continued climbing until late 2011. While stocks were still nursing losses from their peak in late 2007, gold was up over 100%. From its low 10 years prior, it was up over 500%. The companies that mine for gold? They were up over 1000% as measured by the Gold Bugs Index. However, that dominance didn’t last. From the peak in 2011, gold is down over -30% and miners more than -70% nearly seven years later.

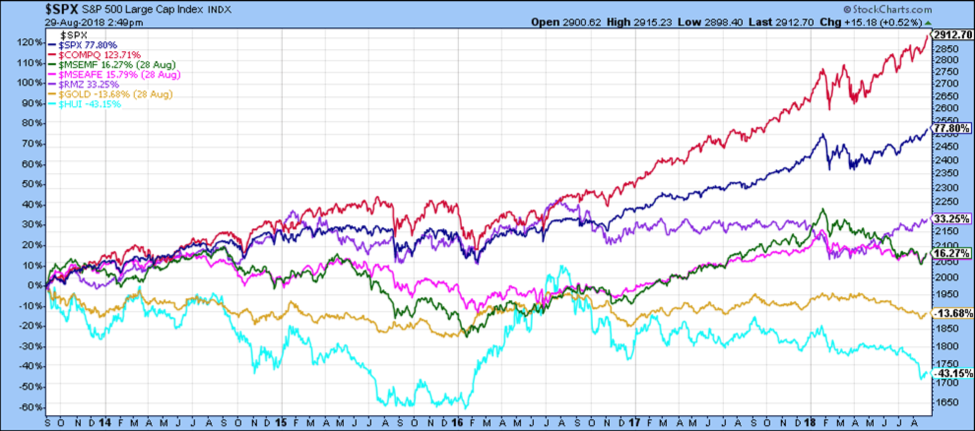

- Finally, U.S. stocks – Since 2013, their performance has dominated most other investment categories. They have clearly been the standout performer even among other stock categories such as international and emerging markets. Should we extrapolate this price dominance out another 3,5,10 years? Well, our brains are compelled to, but we cannot. Similar to all the other “favorites” we’ve discussed, U.S. stocks will most likely be one of the worst performing investment categories going forward. Categories that outperform today almost always underperform tomorrow. In fact, looking at the examples we’ve discussed, one would have been much better off in the late stages investing in just about anything but that category that was doing the best.

Below we can see some of the categories we’ve been discussing coming into the tech bubble in 2000. While the answer seemed obvious to most, what would have happened if we overrode our brains, resisted the urge to invest in the Nasdaq and instead bought the worse performing categories? We would have bought emerging markets, real estate, gold, and gold miners (just looking at the same asset classes discussed). It’s important to note that performance for the first two categories was basically 0% for the three years leading up to the market peak, while it was deeply negative for the latter two gold categories. (See below).

Five years later, the painful decision to buy the underperforming categories would have already started paying off, while those who extrapolated the great gains in the Nasdaq would still be down over -50% from the market peak. It would take a 100% gain for those investors to get back to where they were.

Ten years later, that decision would still have paid off. The four best performing categories were in fact those that were the worst performing in 2000. Those that were the best performing in 2000? Well, they were still at the bottom of the pile ten years later. Buy low, sell high – as difficult as it is to do in real time would certainly have been a good axiom to follow in 2000.

So where does that leave us now? Well, if we can avoid falling victim to hindsight bias and playing the extrapolation game, we’d probably be best served looking to buy what’s relatively cheap and avoiding what’s expensive. That would mean minimizing exposure to U.S. stocks and investing in greater weight into gold miners, gold, international stock, emerging market stock, and real estate – in that order (see below). When we apply certain valuation methods to see whether these categories are expensive or cheap relative to what we’d consider reasonable or normal over a long period of time, we end up reaching a similar conclusion. U.S. stocks are in just as big a bubble, if not bigger than the 2000 tech bubble. International and emerging market stocks are actually reasonably priced if not cheap relative to long term averages, while gold miners and gold are very cheap relative to where they’ve traded in the past. Bottom line – looking under the hood at valuation actually confirms what we can see visually and simply below. One is generally best served over time buying categories that have underperformed and eschewing those that have done the best.

This year will undoubtedly be one that proves critical for most investors. As much as it feels like we’re facing issues and circumstances that are completely new and unique, and we are, the way those things manifest in markets is very commonplace. Certain investment categories do really well, others don’t. What appears to be an inexpensive, wise choice for the long term could go further down in price before it goes up. As we are all aware, that investment which we should be avoiding like the plague will always go up a bit further before gravity prevails – sometimes a good amount further as the Nasdaq did in the late 90’s, gold in its final years, and now U.S. stocks. We’re well beyond that point where gravity should have prevailed given valuations, potential geopolitical triggers, etc. Just because it hasn’t yet, doesn’t mean it won’t. In fact, the exact opposite is true. History tells us that the larger the elastic is stretched beyond what is normal, the larger the eventual snap back.

Along those same lines, the larger the underperformance of a given investment category, assuming its merits haven’t changed materially, the greater the potential when that underperformance reverses course. This is precisely why we began overweighting international and emerging market stocks a few years ago and gold and gold miners more recently. Although they like anything else will experience ups and downs over the short term, they are much better positioned to serve our goals and objectives over the longer term. Buy low, sell high has never been more important than it is today. One cannot let relatively short-term price behavior influence long-term investment objectives. At least not if they’re effectively executing on the buy low, sell high concept. Manic markets are very good at encouraging bad behavior and casting doubt on responsible courses of action. Don’t fall for it.