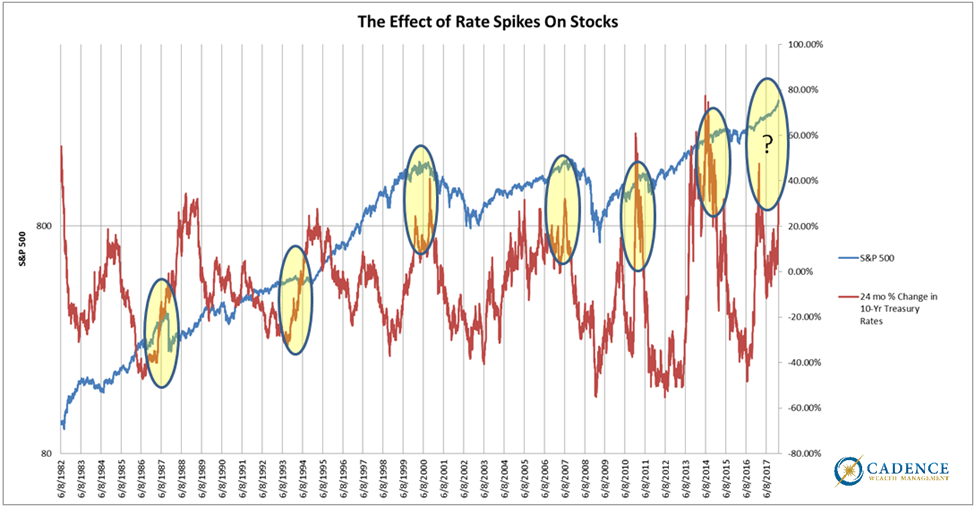

Bubbles are dynamic and as a result, different each time. But one common theme amongst them has been the tendency for interest rates to play a role in their eventual demise. Looking back 30 years, there seems to be a causal relationship between rising rates and poor stock market performance. More times than not when the 24-month change in 10-year treasury rates spiked upward, stocks ran into trouble. Practically every sizable correction in stocks was preceded by an acute increase in interest rates.

But rising rates don’t just signal possible trouble for stocks, they also mean there’s a current problem with bonds. When rates go up, bond prices come down which means they are losing value within an investment portfolio. This creates a dilemma for investors since gains, of course, are preferable – especially when everyone’s getting filthy rich investing in stocks.

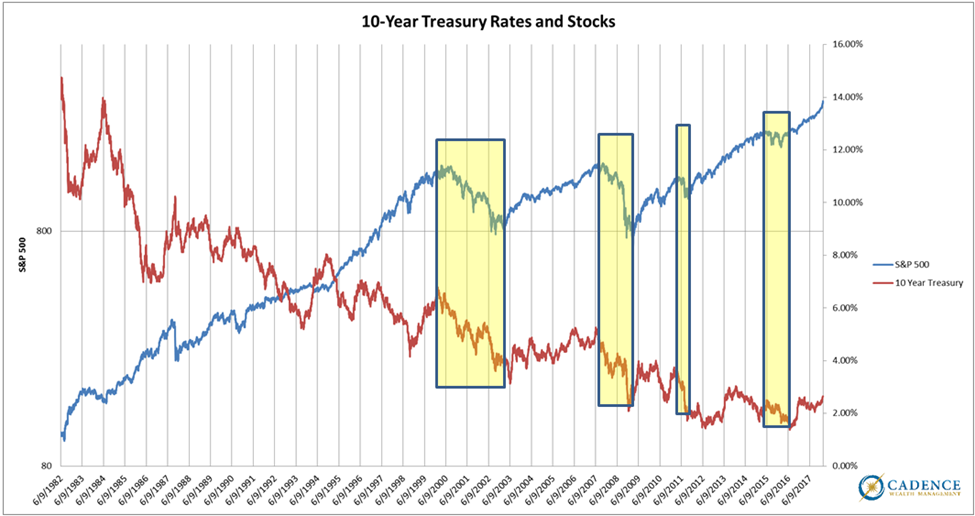

However, since we never know how far rates will rise, these losses may be a small price to pay to be in the right spot when the stock market finally rolls over. The chart below highlights what happened to 10-year treasury rates during the last four largest stock market declines. This flight to safer investments led to lower rates and higher bond prices each time.

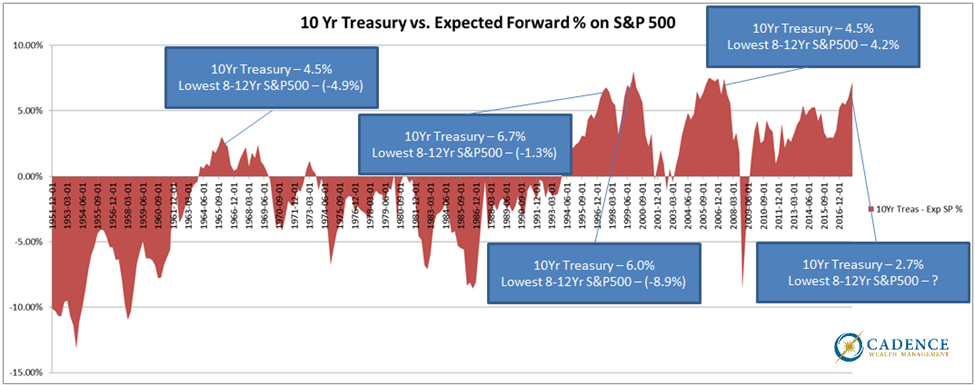

In addition, over the long-run, when market multiples are super high as they are now, bonds become a much better relative option. As we can see below, when the rate of interest we can earn on a 10-year treasury bond minus the total rate of return we’re expected to earn in stocks over the coming 10 years (based on valuation and its historical relationship to future return) is positive, bonds become a pretty good investment option.

In the mid to late 1960’s when stock market multiples were high, investors would have done much better buying a 10-year government bond and holding it; same in 1997 and even in 2005. What’s important to keep in mind is that we’re currently sitting on the highest valuations in history. After this bubble pops, our belief is that not only will bonds have been a far better option today than stocks, but that 2005 through 2007 bond investment would also prove much better than a stock investment from the same starting point. Where stocks are currently higher than they were in 2007, they will be lower in due time.

In short, that 2007 investment comparison isn’t in the history books yet. Looking at an 8-12 year timeframe, we’ll have to see where stocks end up in 2019 before making a final determination as to where investors would have been better off.

Given the weight of evidence and bubble dynamics, we think the smart and safe money should be on bonds winning out in this scenario again, just as they did by a fairly convincing margin in the previous two. As boring as it may be, the bottom line is this; when stocks stand to lose 60% of their value at some point, 2.7% on a U.S. Government bond doesn’t look half bad.