As we draw closer to wrapping up a very trying and difficult 2020 and continue to face tremendous uncertainty around the presidential election, social unrest, job security, life, markets, etcetera, the famous quote from Charles Swindoll comes to mind: “Life is 10% what happens to you and 90% how you react to it.” It’s times like these when it’s important for us to remember this and try the best we can to live it. Part of this message refers to the importance of attitude in dealing with challenges, while the other form of “reaction” is the choices we make in the face of those challenges. With respect to all of the more social uncertainties we’re up against heading into year-end, our challenge to ourselves is to do our best to stay positive and make constructive choices. These things we have full control over. With respect to financial uncertainties, we actually have quite a bit of control over those as well. In the next 10-20 years, we feel strongly that the decisions people make around their investments will make all the difference in their ability to achieve and/or stay financially independent.

Future Returns

Those who invest over the next 10 years the same way they’ve invested over the last 10 will most likely fall well short in achieving the returns they’re after. Sadly, this cohort represents well over 90% of the investing public due to the buy and hold model of the financial services industry, the move to passive index investing, and the general bias of humans in feeling that the future will play out like the recent past. There are certainly more factors, but suffice it to say that these are some of those at work in keeping investors on the same path they’re currently on, regardless of how dangerous that path may be. We’ll refer to this path as the traditional path, and here’s where we see it leading…

The Traditional Path

The traditional path that most investors follow, in large part based on the financial products and rules of thumb purveyed by the financial industry, involves some mix of stocks and bonds. Over the last 40 years, this model has worked very well since both categories of investment have experienced well above average performance. In many ways, this is due to a perfect storm of variables materializing including, but not limited to, persistently falling interest rates, globalization, debt accumulation, financialization, technology driven innovation, and monetary accommodation. It’s been one heck of a run that has taken us to record high stock valuations and 5000-year lows in interest rates. It’s no surprise that models analyzing the last few decades only would see no problem with the current set of circumstances. Extrapolate the last 40 years into the future and all is good. Unfortunately, this isn’t how cycles work. Even the super long cycles like we’ve just experienced in stocks and bonds eventually change and the traditional path that most investors are depending on is long overdue for a massive sea change.

When evaluating the risk or opportunity in stocks over the long term, there are a number of approaches; some complex, others more simplistic. Our feeling is that the truth lies in the simple math; the conceptual. Too many assumptions and moving parts here can obscure the obvious. The first concept we’ll look at is one of price relative to earnings; otherwise known as a stock’s P/E multiple. If it’s low, you can pay less for a certain amount of earnings whereas if it’s high, you need to pay more for those same earnings. There are problems with this approach since earnings are typically highest toward the end of growth cycles, making stocks look cheap, and lowest toward the end of recessions, making stocks look relatively more expensive. With this in mind, it’s important that one takes the growth cycle into account when using the price to earnings valuation approach and understands how the earnings component might change going forward. That said, here’s a real-world example to think about:

Say there’s a café in town that generates $50,000 per year in profit that’s being sold for $500,000. If you’re looking to invest in a business, that would represent a nice 10% return on investment or what’s called an “earnings yield”. Not bad, especially today with bank accounts paying practically nothing and bonds not much more. We’ll come back to that later. Things to evaluate are how sensitive to the economic cycle those profits are, where we are in the economic cycle, other local competition, etc. Fair to say however that a starting earnings yield of 10% leaves some margin for error.

Now imagine that same café was selling for $1,250,000. The profits of $50,000 now represents only a 4% return on investment which leaves a much lower margin for error in the event profits decline. Looking at investing this way makes it much easier to declare whether something’s expensive, cheap, or reasonably priced. Stock markets today are valued very closely to the café in this latter scenario, and that’s before the impact of the economic downturn we are in the midst of, which means the earnings and earnings yield are heading even lower. Expensive and risky. There’s really no debating it.

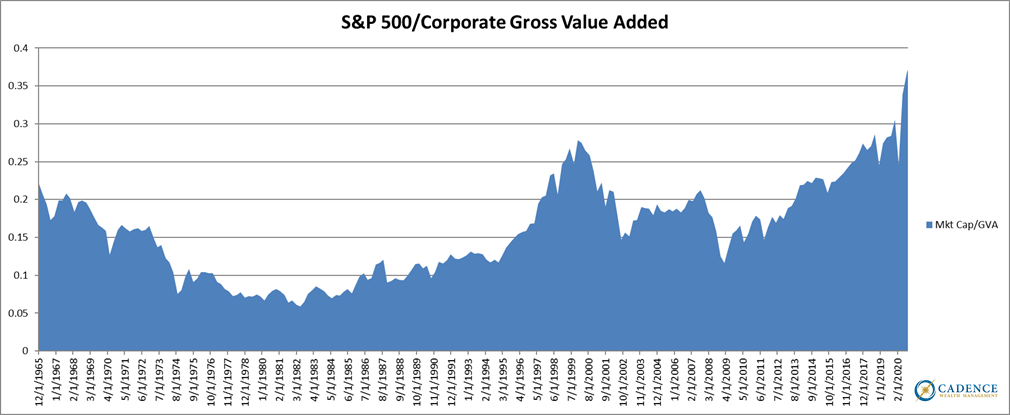

The second approach is to compare prices against something else that plays a longer-term role in supporting them such as economic output, national household net worth, corporate sales, etc., and then to look at the historical relationship of those two things. We’ll use a form of corporate sales called corporate gross value added to get a sense as to where stock prices are relative to the amount of stuff produced or services provided by the underlying companies.

As you can see in the chart on the next page, the relationship between stock prices and the underlying stuff and services being produced and sold is off the charts. We’ve eclipsed one of the most speculative episodes in history, the late 90’s tech bubble, which makes today’s stock market unrivaled. It’s important to remember that it’s this performance achievement that most use as justification to continue to invest traditionally. It’s worked therefore it always will. Using this same logic, in the late 70’s investors could have also assumed that stocks were broken, so they always would be. That’s precisely what they did and the famous August 1979 Business Week headline “The Death of Equities” captured that sentiment perfectly. What subsequently happened is that stocks went on to achieve one of the best 20-year performance stretches in history because they were so cheap for so long and eventually the cycle turned. We fully expect a similar experience over the next 10-20 years, only in reverse. This cycle will also turn, and we continue to believe there’s a good chance it started to in late 2018 (as we’ve recently written about).

To add a little context and math to this point; to get back to the average relationship between stock prices and corporate gross value added since the early 1960’s, the S&P 500 would have to decline to 1,473, or -57% lower than it is now. If we assume corporations grow sales by about 4% per year, and pay 1.5% in dividends over the next ten years, the average expected level of the S&P 500 would be just under 2,200, approximately -35% lower than it is now. This would not be a good 10-year return for the stock market and as unlikely as it may seem, there is ample precedent for this here in the U.S. and abroad. It is not only possible, but entirely likely based on prices that are simply far too expensive to lead to anything productive over a long enough stretch of time. What fools people into thinking this time is different, every time, is that valuation alone does not mark a turning point. Things have a tendency to get more and more expensive just as they do more and more cheap, until the cycle suddenly and oftentimes inexplicably changes. It’s over longer periods of time that valuations are instructive. The good news is that most investors invest for the long term; thus, all of this should matter a great deal.

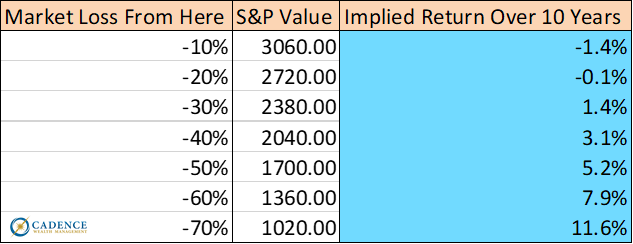

When might stocks become attractive again? The chart below would suggest that future returns on stocks start to look decent after about a -50% drop from here. Based on a reasonable growth assumption for corporate sales and a historically average relationship between stock prices and that ending corporate gross value added (sales) figure, after a -50% drop in stocks from roughly 3400 to 1700, the expected annual return that would bring stocks in line with corporate sales activity 10 years from now would be ~5.2%. Still not what most would expect, but better than what the bank’s offering by a long shot. This would get our local café down to a selling price of ~$625,000, which would probably start to pique our interest. Probably.

And what about bonds? This one’s pretty straight forward. Interest rates on bonds across the spectrum are at historical lows, which means if you buy a 10 or 20-year bond, you’ll get paid very little along the way before getting your money back (hopefully) at the end of the term. With 10-year U.S. Government bonds paying 0.77%, you simply aren’t adding much to portfolio returns over the long term by having them in the mix. Riskier bonds you may ask? Although you’ll earn more interest on riskier corporate bonds, you face insolvency risk and stand to lose some principal along the way as companies that extended themselves too far declare bankruptcy. This is already happening at record levels and is beginning to eat into any extra interest investors are getting over and above the safest, lowest interest bond choices. The conclusion and harsh reality here is that bonds will not provide investors the level of returns going forward that they’ve been accustomed to getting.

This is the traditional path. It looks very similar regardless of the mix of stocks and bonds simply because the return prospects for both broad categories are equally unimpressive. Whether 20% stock and 80% bond or the inverse, the next 10-20 years will likely look nothing like the last 10-20. If you’ve made it this far and follow our logic, then consider yourself enlightened. Most aren’t and won’t be until they’re much too far down the traditional path. This is really unfortunate and it’s a big part of what drives us to educate all who are willing to take the time to listen and learn, whether paying clients or not. What has already materialized and is yet to play out in markets is the “10% that happens to you” piece. How we adjust to what’s happened and prepare for and deal with what’s coming is the “90% how we react to it” part – the making the best of it. The pursuit of a different path.

The Untraditional Path

If we believe in cycles, reversion to the mean, gravity, and math, we know that there’s a very good chance that over a long enough period of time, 10-20 years in this case, the traditional stock and bond approach to investing will not deliver the returns that we need them to. When it comes to finding a plan B, we must apply the same logic to help us identify better investment choices as well as a process to help us apply that logic and manage ups and downs along the way. A good place to start might be to ask the question, “If stocks and bonds are expensive and unappealing, are there asset categories that are cheap and attractive?”; and by extension, “If stocks and bonds are toward the end of their respective upward cycles, are there categories that are near the beginning of theirs?” Although most traditional investment categories are expensive this time around, there is one that has been left behind over the years; commodities. We’ve talked about this in prior letters, about how commodities relative to financial assets are historically cheap. They haven’t performed well in recent years and as a result have received little interest from investors. This creates somewhat of a feedback loop which perpetuates the cycle until something breaks it. Sometimes that something is simply a few random factors that gets prices moving upward coupled with investors looking for better opportunities. Mix it all in a fire-cooked kettle and poof, you have the makings of a cycle transition. We could wax on about global supply and demand factors and the future of infrastructure projects globally, but sometimes it’s really that simple. Things that have gone down a lot for a long time start going up again simply because they went down a lot for a long time.

For this reason mainly, in addition to some other debt, currency debasement, and inflation related ones, we believe commodities and more specifically, precious metals, have a very good chance of following a different path over the coming years than stocks and bonds. Make no mistake, rising commodity prices leads to inflation and inflation in no way adds to the average person’s standard of living. From a big picture standpoint, falling asset prices and rising commodity prices is not a very comfy situation for society as a whole and we’d prefer that both ebbed and flowed within more modest, reasonable ranges. Unfortunately, yesterday’s extremes create tomorrows extremes, but in the opposite direction and from an investment standpoint, we have the ability to lessen the impact of that on our lives. Commodities offer a chance for a different path.

In addition, following a process that can help one impart discipline around when and when not to take some investment risk can help tremendously over the coming years. For example, very few of the below average multi-year return periods in markets consist of low returns every year for say 10 years. Rather, markets usually drop sharply from expensive valuations over months and bounce back upward over years. In some cases this process of sharp drops with recoveries happens multiple times over a decade or two. This was certainly the case in the 1930’s, the 1970’s, and most recently in the 2000’s. If one has a system or discipline to help them decrease risk and exposure to loss when markets are more expensive and to increase risk or exposure to potential gains when markets are more reasonably priced, paltry long-term market performance isn’t necessarily what an investor has to experience. By managing risk along the way, one could do better than if they simply bought and held regardless of price. This concept should absolutely be a part of every investors process going forward. The days of buying and holding being the superior strategy are very likely coming to an end. Again, if one loses -50% as stocks move back toward more normal valuations, he or she needs to gain 100% to get back to even. This could take a while, especially if there are a couple doses of this along the way. For perspective, Japanese investors who bought and held at the height of their bubble in late 1989 are still waiting to get back to even more than 30 years later. It can and does happen. Risk management will matter tremendously going forward.

If we combine the two of these concepts, holding more of the stuff that is valued attractively and closer to the beginning of its cycle as well as risk managing all asset classes as we go, the market’s outcome doesn’t have to be our outcome. Not only is there hope, but there are things to feel excited and optimistic about. The key however is not attempting to seek safety within the herd. Most investors will continue to do what they’ve done and invest in what’s been working. That’s absolutely fine if we’re bouncing around within normal price levels and those things that have worked are sustainable. The extremes however aren’t sustainable and most fail to see that until it’s too late.

So, while the herd continues running down the traditional path expecting to find the same results, it’s our strong belief that those results lie down a different, more untraditional path. Sure, its entrance may be covered by a few stray branches and it may not be as well-lit as the other, but based on all the maps available to us, it seems a much more direct route to where we’re looking to go. We have more control over this situation than we think, but it starts with understanding some key investing tenets:

-

- Cycles – Where we are in the cycle has a very big impact on investment outcome. Starting low increases our chances of ending high and vice versa.

- There is no rule saying you need to own lots of stocks and bonds at any given point in time. This model portfolio rule of thumb was largely built on the last 40 years of market experience consisting of arguably the strongest stock and bond markets ever. The stock/bond model portfolio concept does not adequately account for nor prepare one for what could be weak stock and bond markets simultaneously going forward.

- Be willing to utilize alternative asset classes when appropriate.

- Keep valuation in mind for long-term investment decisions.

- Have a process for helping you risk manage the ups and downs of cycles going forward. Just because markets may be flat to down over 10-20 years, this doesn’t mean you must be.

- Finally, don’t seek confirmation from the herd. If you want to achieve a different result than most going forward, and you believe as we do that the traditional path is likely to be disappointing, then you must deviate. At extremes, the herd is almost always wrong, eventually. And the extent to which they are wrong usually more than offsets the gains accrued from the short period of time they were right. Timing we can’t control, but our decision not to leave this to chance, we can control.

Failing Together

It’s worth mentioning that as humans, it’s often easier to fail if there are others failing along with us. This is true in all aspects of life. It’s why some people prefer team sports to individual sports. It’s why some prefer group projects to solo projects. It’s why our default setting is to want to invest the same way others are. Sure, we hope to win, but if we lose, we can’t be blamed or criticized by others or more importantly, by ourselves when others are losing too. We can live with the mistakes we know others made as well. Just as there are many investors that resign to this way of thinking and continue to invest in the markets without regard to valuation, there is also a whole financial services industry that does the same. There is not only profit in encouraging investors to continue investing regardless of price and risk, but there is job security in it knowing that if something goes wrong, everyone’s in it together. We completely disagree with this line of thinking. We would rather be temporarily wrong and alone in trying to do the right thing, than lose significantly over time along with the masses. If most investors knew the probability of earning less than 0% over the next 5-10 years by investing in a stock ETF, there’s a good chance they’d take a pass or invest differently. The failure of our industry to point this out and make it clear to investors is disappointing. Attempting to obscure or hide that risk is worse. In any case, the key thing to understand here is that although stepping out of the box and choosing a less popular path may feel risky, it’s often times just the opposite, so long as it’s done for the right reasons based on sound analysis and logic.

Moving Forward

There is much we can control. Our attitudes. Our decisions. Our ability to deal with failure and adverse outcomes, learn lessons, correct mistakes, and do better next time. There’s going to be a lot thrown at us over the coming days, weeks, and months where this applies. The alternative is anger, poor choices, and repeated failure. We are in full control of our reactions and decisions and in making sure our next one is the best one.

There are also many challenges we face as investors over the coming years that we can either deny are real and later classify as unavoidable, or take control over now in an effort to change our course. We are incredibly optimistic for those on the untraditional investment path of alternative investments coupled with a sound risk management process along the way. Our goal is to help everyone identify the difference between the two paths and make the best, most informed choices possible. But it’s important to keep in mind that it’s dynamic and agnostic to investment type. It’s also objective and unbiased. We will likely be excited about things two years from now that we aren’t currently and vice versa. When the facts and situation changes, it’s our mission to change along with them. We’ll continue to do our best as a firm to take control over the things that we can and help our clients do the same. As long as we’re resolute about this, we’ll be fine. In fact, not only will we be fine, there’s a good chance we’ll thrive.

Editors Note: This article was originally published in the November 2020 edition of our “Cadence Clips” newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.