Saturday Night Live fans may remember the skit where Bruce Dickinson (played by Christopher Walken) helps Blue Oyster Cult nail the recording of their hit “The Reaper”. It’s a great cast of actors in this bit, but Gene, played by Will Farrell, has the leading role in his struggle to inject just the right amount of cowbell into the song. After a number of abrupt breaks in recording initiated by the lead singer, who grows increasingly agitated by the incessant banging behind him, Christopher Walken (in the character of Bruce Dickinson) in his one-of-a-kind delivery first proclaims “I gotta have more cowbell, baby!”, then later in the dialogue, the gem: “I got a fever, and the only prescription is more cowbell!” I would encourage everyone whether a fan of SNL or not to watch this skit. It’s a classic comedic gift from the year 2000, and yes, Jimmy Fallon laughs as he’s delivering his lines. It’s all there.

What’s interesting about this sketch, is that it serves as a handy metaphor for what we’re experiencing in financial markets today. Cowbell would represent stimulus in the form of central bank liquidity injections and government fiscal spending. The band represents free markets and the bottom 90% of the population, growing increasingly agitated and disillusioned by it, regardless of whether or not they’re aware of cowbell being a cause of this angst. And those at the top of the asset pyramid who have the most to lose if fair pricing and socioeconomic equality revert back toward more balanced levels, are Bruce Dickinson. The only prescription for their fever is more cowbell. We’ll leave alone the fact that this sketch aired in April of 2000, just after the peak in what was the biggest bubble of all time up until now. The metaphor back then couldn’t have been more apropos. As for now, 2021 will likely see large market participants making the same demand they did in 2020 and in a handful of years prior. “I gotta have more cowbell, baby!”

Beyond the Point of No Return

When a child who’s just done something wrong is put on the spot, the immediate reaction is to deny, fib, or outright lie about what just happened. It starts out innocently enough and the motivation behind it is usually understandable – the fib can help avoid embarrassment, recourse, or punishment. What most of us have learned from experience however, is that the longer that course of action is stuck to, the fib that is, the harsher the punishment will eventually be when the truth comes out – and it always does. In many ways, central bank manipulation of money and markets is analogous. This isn’t to say central planners began all of their policies with a lie, quite the contrary in fact. Intentions may have been pure – keep the economy moving forward and people employed. Along the way however, we’d argue that inconvenient outcomes have been increasingly ignored, omissions of truth have been made, and in some cases we’ve witnessed outright denials as to the impact monetary intervention has had on free markets and the societal wealth gap. It’s become clear that for central bankers to admit the flaws and negative consequences of their policies and reverse course in some way, they would have to be willing to let financial markets stand on their own two feet. After more than a decade of monetary steroid injections and the extent to which the economy depends on asset prices not only remaining elevated, but continually rising, there is virtually no chance that policy-makers would consciously choose to withdraw support. The repricing based on natural supply and demand factors as well as institutions and investors assessing risks to their own capital without the possibility of future bailouts would be extensive. What started off as relatively well-intentioned and benign interventions has morphed into something much more serious. This is the equivalent of a child doubling or tripling down on the lie because they know the punishment would be far worse than coming clean. The point of no return.

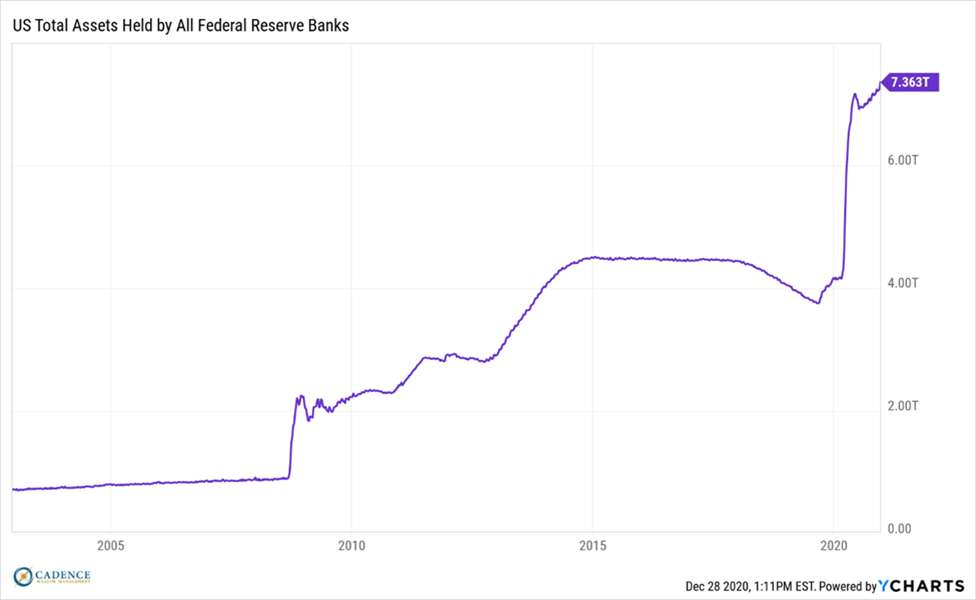

Below is a chart of all assets held by federal reserve banks, which is the inverse of the cash or “reserves” they’ve placed in the accounts of member banks held at the Federal Reserve by the click of a button. There are some mechanics behind this that matter in terms of what can be done with that money, but the larger point is that most see this as stimulus and support for markets, and so it serves that purpose. The level of that support for markets has increased more than 7x since before the global financial crisis in 2007 – not insignificant.

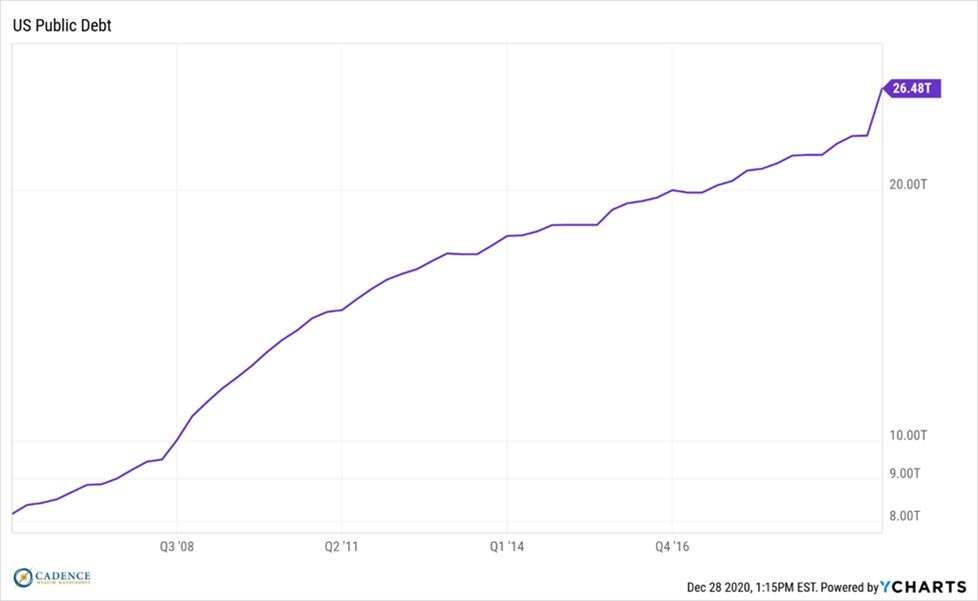

At the same time, U.S. government debt (chart on following page) has tripled and now stands at more than $26 trillion. What’s most notable about the values in these two charts is that they’ve exploded higher throughout a period of economic growth – a supposedly prosperous time. Generally central banks inject liquidity and governments deficit spend in order to pull an economy out of recession and get things moving again, but here we’ve managed to add more leverage in both categories before that longer economic downturn has even arrived. What this suggests to us is that either economic growth would have been much worse had we not done these two things over the last decade or that economic growth was slightly below average – ~2% over the last 10 years – in part because of them. Either way, what’s pretty clear is that we’ve crossed the Rubicon with respect to debt and fiscal restraint. In an effort to avoid market dips and economic slowdowns, we’ve gotten ourselves beyond the point of no return, where it’s no longer realistic to expect debts to be paid back. This realization will likely have large implications as we move into 2021 that investors need to be aware of.

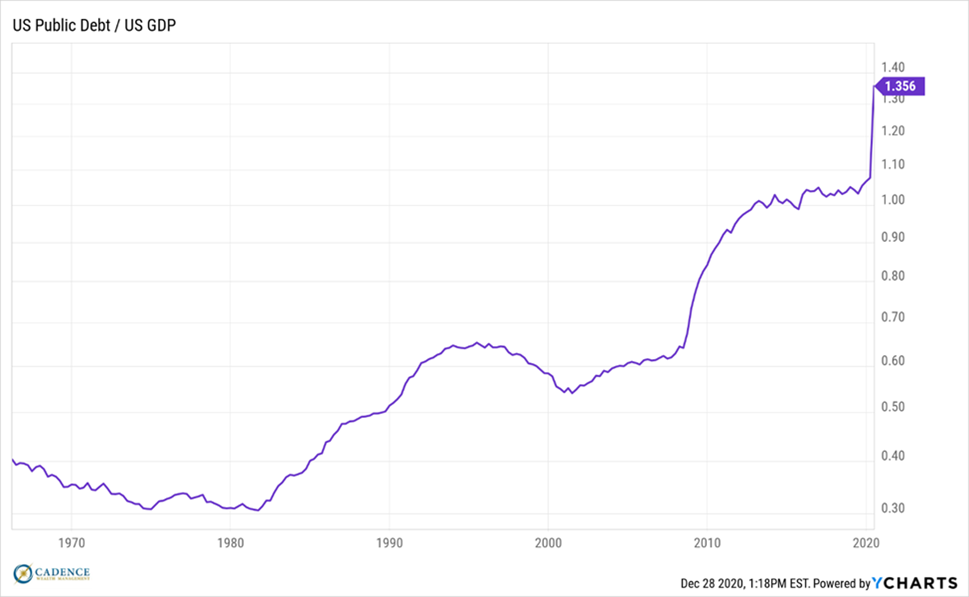

Our debt to GDP (national income) is now above 130%, a level that barring explosive economic growth, is very difficult to come back from (chart below).

Ramifications for Growth and Inflation

A good understanding of financial history can help us make sense of what we’re seeing and where it might lead, but we also have to acknowledge the fact that much of what we’re experiencing now is new and different. There is no way to know for certain where any of this will lead. The best we can do is blend what we’ve learned from the past with a good dose of common sense. A Bayesian approach where we learn and adapt in real time is also crucial, lest we get our heads stuck in the theory of what should be rather than what is.

With that in mind, we know debt can be stimulative at first as it leads to spending – this is fairly easy to observe. Over time however, excessive debt leads to a diversion of cash flow toward servicing that debt rather than more productive investment/uses. Richard Koo, the author of The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics talks about excessive debt leading to balance sheet recessions where economic downturns are extended in length because the private sector becomes focused on paying off debt rather than spending or saving. This takes place when borrowers, after learning tough lessons about the perils of excessive debt by way of a negative market event or recession, vow never to fall into the same trap again. One could certainly argue that we run the risk of another balance sheet recession just as we did in the Great Depression, after the Global Financial Crisis, and as Japan did for years after it’s asset bubble burst in 1990. Koo argues that staving off recession is more about governments stepping in and spending when the private sector isn’t rather than central banks approaching things from the financial markets angle. As we’ve written about before, it comes down to what it is that we’re trying to rescue; the economy or financial markets? If as Koo argues, we try to save the economy through government borrowing and spending, markets reprice and eventually come back. Most important though, the average person has a job and can maintain a reasonable existence. If, however, we choose more of a trickle-down approach where we prop up financial markets in the hope that it creates a “wealth effect” that supports the economy, the long-term outcome could be quite a bit less desirable. That course might lead to the rich getting richer on top of a hollowed-out economy saddled with debt. By encouraging the private sector to take on more debt, it becomes increasingly unwell and less able to adapt, grow, and employ. This has been our course for years and explains a lot about where we are now. Our next recession may well lead to the type of balance sheet repair that Richard Koo talks about given the amount of debt currently heaped on top of the private sector. With the U.S. government already at over 130% debt to GDP, their ability to step in and fill the void while the private sector pays down debt could well be limited.

In applying both the Bayesian method and common sense to this whole debt discussion, we know from the past 10 years that record borrowing did not lead to rapid economic growth, but rather below average growth. It also makes sense that when overall debt levels get too large, less cash flow can go toward consumption and investment since it’s being gobbled up by interest payments. Thus, we expect growth will be well below average going forward. There will of course be cyclical bounce-backs in response to contractions that register on the Richter scale, but on average, over time, economic vibrancy is likely to disappoint until debt levels get reigned in. Similarly, we also expect that unless the method for stimulus delivery changes, inflation will also continue to be lower than authorities would like to see. If there is too much debt, little productive investment, overcapacity, and a maniacal focus from Wall Street on keeping corporate profit margins high and thus wages and personnel costs low, inflation will continue to make only periodic cyclical appearances rather than a lasting secular one. This could change however.

How Does Debt Get Resolved

In free markets, recessions reduce debt levels either by forcing private sector bankruptcies or by making things so difficult for the indebted that they place newfound importance on keeping their liabilities low and prioritize repayment. In today’s markets where bankruptcies and taking losses are verboten, there are two methods of dealing with excessive debt. First, extend and pretend. Refinance the debt and worry about it tomorrow. It’s fairly obvious that this equates to kicking the can down the road and is not a viable long-term solution. The second solution is to generate inflation. By increasing the dollar value of profits and wages through inflation, the fixed value of debt becomes relatively less and more easily paid back. This of course is theoretical and assumes that no further debt is accrued at the same time. It also assumes that profits and wages are rising faster than the cost of goods and services, which of course is also entirely theoretical. To us, this solution is not only completely irresponsible and dangerous from a societal perspective, but has a very low probability of actually working. It is, however, the choice our leaders are making and it has fairly extensive investment ramifications.

Big Picture Theme

As it stands now, central bank intervention and government fiscal stimulus is likely deflationary in the long term. For the duration of the experiment globally, it has yet to create enough inflation to solve the world’s debt problems; rather it has made them unambiguously worse. As a result, financial markets have continued to rise due to low interest rates, a lack of productive real investment as an alternative, and the speculative fervor created by endless bailouts and increasing leverage. This may well continue into 2021. However, since we established that more debt makes growth prospects and economic vibrancy worse, we can safely assume that the foundation underlying the financial markets is even more unstable than ever, and as a result, not sustainable. Something will need to happen before meaningful, lasting growth returns to the economy. Either excessive debts get wiped out the old-fashioned way via market declines and recessions or the government succeeds in creating inflation. Both of these scenarios have us favoring real assets over financial ones.

John Hussman of Hussman funds does a great job breaking down and articulating why valuation matters over the long-haul. It really does come down to returns over a 10 to 15-year stretch being determined by the price one pays up front. In the short term, who knows, but longer term, valuations matter. Hussman also points out that low interest rates shouldn’t justify higher stock prices. If anything, they merely reflect the poor growth prospects in the economy going forward. Viewed this way, stocks look even more expensive now than they normally would given the low growth prospects we’ve discussed. We continue to believe there are big issues lurking in financial markets as we move into 2021. Investors need to be very careful about the risks they are taking.

The alternatives to stocks and bonds are cash and real assets such as real estate, precious metals, and commodities. These categories are historically very inexpensive not only compared to stocks and bonds, but in some cases on an absolute basis as well. They’re also particularly appealing given the two potential outcomes we’ve highlighted; either a good old-fashioned market contraction/recession or a change in policy to actually generate inflation. We discussed in a recent newsletter the prospects for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) where the Fed and Treasury essentially become one and the same. Rather than the financial markets lending money to the Treasury (government), this would allow the Federal Reserve to lend to the Treasury directly (potentially without repayment expectations) which would equate to new money entering the financial system through government spending with no investment offset to balance it out. Truly printed money, which would very likely generate the type of inflation that nobody in the real world and not perched in an ivory tower wants. This, in addition to the favorable cyclical factors, makes real assets and commodities an incredibly attractive theme over the coming years. 2021 may well capture a portion of this theme playing out.

Navigating Interim Cycles

What’s so difficult about investing is that even though something is likely to play out in the long term, something else entirely might be happening in the short term. In some cases, near-term movements can be explained by cycles, money flows, intervention, etc., while in other cases they’re just noise. These movements can be jarring and cause us to doubt our original thinking if it’s not grounded in a process that helps blend the long and short-term market movements. To this end, we place a high degree of importance around understanding the shorter-term fluctuations of growth and inflation cycles regardless of our longer-term outlook. Nothing ever moves in a straight line up or down.

Even if we feel markets will be lower in 1-3 years from where they are today, that’s not to say they couldn’t be higher over the next 3 to 6 months. F. Scott Fitzgerald is quoted having said, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” We’re not suggesting that we possess first-rate intelligence, only that it’s important to keep an open mind – especially over different timeframes.

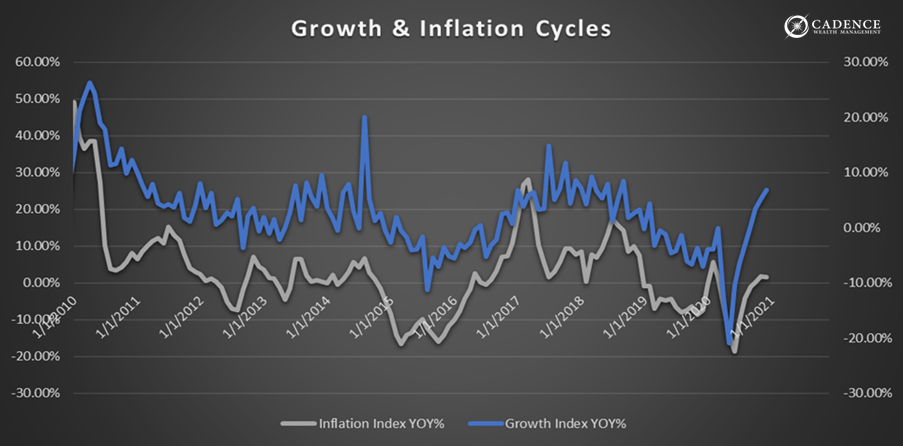

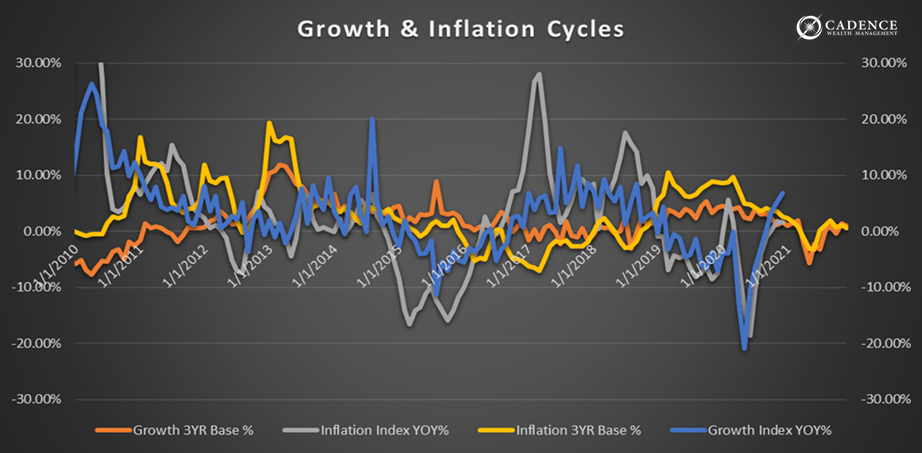

Below is a chart of the rate of change of growth and inflation from one year ago. We can see that after trending lower since late 2018, they both experienced a sharp bounce off of the lows in the spring of this year. It’s no coincidence that stocks and bonds also recovered along with the economy.

If we look at the second chart below, we can see the addition of two lines that represent base effects for both growth and inflation (orange and yellow respectively). These indicate how much harder or easier it will be mathematically as we move forward to grow from year-ago levels. You’ll notice that the base effect lines bottom out around June of 2021, which indicates the levels we’ll be comparing against continue to get easier and easier to “grow” from until June. At that point, the math reverses and it becomes increasingly harder to accelerate at a faster rate. These base effects can not predict the future, but they do indicate how easy or difficult it will be for a trend to continue in either direction. The bottom line here is that looking at the base effect alone, there is a mathematical tailwind for a continued rebound in economic growth and inflation until mid-2021 in rate of change terms. At that point, things get much more difficult.

Because the math of base effects can only tell us so much, we also have to keep a finger on the pulse of markets for clues as to whether either of these cycles could reverse direction sooner than anticipated. Covid certainly has the potential to change this as does any number of things. We can never be wedded to any one course of action, especially in today’s environment. If one thing is clear from all of these charts however, it’s that the cowbell has led to a sharp recovery in asset prices across the board. This has a reasonable chance of continuing into 2021, but it wouldn’t surprise us to see the beneficiary of that cowbell begin to transition from financial assets more toward commodities. We’ve seen this in precious metals beginning in late 2018 and more recently across the rest of the commodities complex in the last few months of 2020. We’re watching for this trend to continue going forward.

Summary

It’s probably best to summarize our clearest thoughts on 2021 in bullet form. So here goes:

- Given the level of stimulus injected into the economy and markets in 2020, along with the easing base effects for year over year change in growth and inflation into the middle of 2021, we would not be surprised if markets continued to do well in the first part of 2021.

- The second half of 2021 poses bigger risks to growth and inflation and converges with our longer-term outlook of most stock and bond categories being susceptible to large losses due to valuations, debt levels, and length of market, business, and credit cycles.

- We are likely to see further developments in 2021 that should indicate how close we are to stimulus taking on a different form. If MMT draws closer to becoming a reality, we would expect commodities to appreciate even more than they otherwise would in anticipation of lasting inflation.

- Social issues will continue to be front and center in 2021 as a result of the economic divide. There has been no progress or serious discussion around changing this from either side of the political divide. This is because as Peter Atwater, president of Financial Insyghts observes, wealth inequality isn’t a left/right phenomenon, but rather an up/down one. Those at the top must be either willing or forced to initiate meaningful change on this front. It has very little to do with political affiliation. Since folks tend not to give up power or money voluntarily, this means civil unrest will probably increase in volume and frequency.

- We believe the largest investment theme for 2021 will be a continued shift from financial assets to real assets; namely commodities. We will continue to position our clients to participate in the growth associated with commodity price appreciation and seek to minimize risk associated with investing in one the largest financial asset bubbles in history.

Although few things can be said with certainty, there is one thing that we will surely hear in 2021: “I gotta have more cowbell, baby!”- and markets will continue to get it. There is no alternative in the eyes of policy-makers. But, will 2021 be the year where markets go where they want to rather than where central planners tell them to? We don’t know. Although it seems impossible for markets to disobey their marching orders, we can’t forget that in 2001-2002 as well as 2007-2008, markets did just that. Regardless of intervention, financial asset prices adjusted considerably until for one reason or another, they finally stopped going down. The same thing happened in Japan over decades. It’s really only most recently that planners have exerted such control over asset prices seemingly on command for so long a period of time. This should get one questioning whether we’re witnessing the exception rather than the rule. The illusion of control.

With respect to sharp market drops and protracted bear markets, the same risks exist today as have in all other economic and market cycles despite our conditioning not to expect them, and it really will be those investors who ignore them that get hurt the most down the line. We will invest in those things that make sense both over the long and short term and adjust accordingly along the way. There will be bumps no doubt, but we’ll endure given our trust and faith in a sound process that draws on history, common sense, and math. It’s times like these that it helps to remember the quote by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin; “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” It’s when things seem like they can never change that change tends to happen, quickly. Although we see some opportunity for growth in 2021, we are expecting, and are ready for, anything.

Editors Note: This article was originally published in the January 2021 edition of our “Cadence Clips” newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.