In the decade leading up to the 1989 peak in the Japanese stock market, there was little to complain about. Almost everybody with shares of stock or real estate was watching their net worth rise, month after month, nearly uninterrupted. It became so easy to make money in the stock market that work ethic declined, leisure time increased, and many corporations found it easier and more profitable to augment their core business activities with stock market activity. According to Edward Chancellor in “Devil Take the Hindmost”, “Japanese politicians were not solely guided by public duty in their desire to support the stock market. They also maintained a private interest in its continuing ascendency”. Virtually everyone with money to invest across Japanese society was playing the stock market game, and the wealth it created rippled into other asset markets. By the end of the 1980s, the gearing of the Japanese economy was largely powered by the stock market, rather than the more typical and fundamental relationship of economic activity driving stock market returns. That was to finally change in 1990 as the horribly bloated Japanese financial system began its long recovery toward something more recognizable, healthy, and sustainable with the Japanese stock market losing over three quarters of its value by 2003. This massive asset deflation helped to reclaim a system that incentivized hard work over gambling, financial discipline over profligacy, and true material wealth over the more ephemeral paper variety. It’s more common to use the term correction for this sort of thing, but recovery seems appropriate given how distorted the system became and its need to reclaim health. Although paper wealth evaporated over time, the deflation of asset prices and disinflation of consumer prices arguably improved the standard of living of those without high income and asset levels as daily expenses moderated and assets became more affordable to own. All it took was a decline of ~-80% through 2008 and a 35-year period of markets being underwater. The Nikkei index is currently right around where it was in the final days of 1989, which is to say, a buy and hold investor buying the Japanese market 35 years ago would just now be getting back to even.

What we can be nearly certain of is that very few investors saw this coming. A bad year or two, defined as low single digit returns, maybe. A negative performance year at some point in the future, possibly. But an -80% decline in stocks that would take 35 years to recover from, no way. When so many people are engaged in something day after day, with the perceived benefits being so widespread, it’s hard to imagine the status quo being anything but the norm. That psychological recency bias aside, another reason the average investor didn’t see this coming is because it wasn’t really anybody’s job within the financial system to show it to them. Big banks and investment companies all make money for their employees and shareholders when credit is expanding and money is flowing. To do or say anything that puts that process at risk is well outside of standard operating procedure. Ideally, regulators step in, but only if their incentives align with future investors more strongly than with current actors, which unfortunately isn’t always the case. Government monetary and regulatory authorities are very often found in close proximity to the financial feeding trough. In addition to being in public service positions, they are also human. In the case of the Japanese financial and monetary authorities, after falling asleep at the wheel and facilitating one of the biggest bubbles in history, for a host of reasons, they finally began raising interest rates and tightening credit, sowing the seeds for the eventual market deflation that followed. Only investors who stepped back and recognized the insanity of the situation were able to protect themselves from significant portfolio and balance sheet damage.

(The chart below maps out the journey the Nikkei index took from the early 1980s to present day.)

There are far too many parallels between Japan in the 1980s and our recent experience in the U.S. to feel confident that our situation is unique. Between persistently low interest rates, indiscriminate credit expansion, a market-centric societal shift leading to a prioritization of capital over labor, a rise in speculation and decline in work ethic, and “wealth effect” over tangible, total wealth, the basic structure of the two situations share a resemblance.

The absolutely critical takeaways from the Japanese experience are the following:

- The peak valuation that preceded the 35 years of lost returns was roughly 140% stock market to GDP, which means that the total value of the Japanese stock market was 140% of the value, or 40% larger than one-year’s-worth of Japanese economic output. By comparison, our stock market to GDP ratio is currently around 208%, more than double our annual economic output. Our bubble is bigger than Japan’s was prior to 35 years of no stock market progress; and not by a little.

- Nobody within the financial system is obligated to warn you. In fact, most are financially incentivized not to. In addition, there are myriad reasons why regulators may not step in to protect investors until it is too late. You’ll only hear warning sirens from sources outside of the system, and the responsibility is on the investor to discern which of those sources is credible and trustworthy. That can’t be delegated without ending up right back in the same conundrum; stuck within the echo chamber of the system. This bears repeating – you will never hear warning sirens from the system whose profits depend on you continuing to do what you’ve been doing, in any industry, with respect to anything. If you want to hear heterodox arguments that push against current inertia, aka warning sirens, you have to step outside that system.

It’s important not to look at this phenomenon as negative, deceitful, or nefarious in any way – it just is. In a capitalistic system where products are manufactured with the specific intent to satisfy consumer preferences, there will always be incentives for a company and its employees to sell more of that product. It’s on the consumer to be aware of the fact that a particular company and its employees will always be biased toward recommending their own product over the competitors, even when the competitor’s may be superior, and even when the customer may not necessarily need the product. You can’t blame a Ford salesperson for trying to sell a car. You also can’t blame him for not recommending a Chevy. This is true in every industry. Financial services are certainly no different. The last point I’ll make here is that it all changes when there is intentional deception. Selling a perfectly good stock mutual fund or product at the wrong time is providing a service, even if its purchase is ill advised. Selling a product using deception or a defective product outright with the intent to deceive is a different story. Sadly, this happens. It’s what good regulation is for. It’s also what reviews, word of mouth, and karma are for.

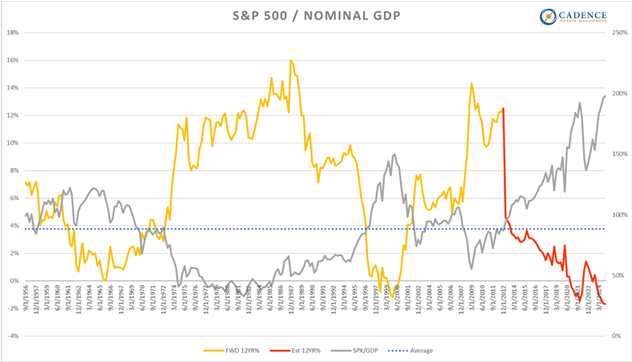

The chart below looks at the S&P 500 relative to nominal GDP and expresses the same relative relationship as the 208% market cap to GDP ratio I referenced above. The gray line plots this relationship over the last 60 plus years, and as is easy to observe, we’re well above the peak valuation we saw prior to the Tech Bubble in early 2000. The yellow line represents the annual returns that investors in the S&P 500 would have experienced over the next 12 years had they invested at various points in time along the way. As you can see, twelve-year returns are highest when investments are made from LOW valuation levels and worst from high valuation levels. The red line is the estimated 12-year return from valuation points over the last 12 years. Most important, from today’s valuation, the expected return based on the relationship between the two over the last 60 years is close to -2% per year. Probably more important, that estimate assumes that markets only revert to average valuation levels. Of course, the average is derived from points above and below it, so it’s fair to expect that returns could be much worse than we’re showing here, just as was the case in the Japan experience and most other bubble bursts in history.

Most people struggle to hold two competing concepts in their head at one time. It creates dissonance. It’s messy – not nearly as simple as we’d like it to be. Binary viewpoints feel cleaner. They save us time. We can turn off our brains sooner – delegate our thinking to others, ironically who’ve often times done the very same thing. Embracing the messiness of existing conflicts, incentive structures, biases is liberating in that it allows us to see things more clearly, operate on a better-lit path, and make more informed decisions. Wall Street and its products can be both great and problematic. Government can do immense good, but also fail miserably at times. Corporations have the power to innovate beyond comprehension and improve our quality of life in untold ways, while also, on occasion, harming us deceptively and intentionally through their products and services. Stocks, and their ability to compound, can create astounding financial wealth while also, at times, destroying it. These things are neither positive nor negative, but just realities.

As we move forward into 2025, we’ll continue to hear a plethora of arguments for why the economy can rebound, stocks can continue to rise, and inflation at a minimum of 2% is still somehow a good thing. We should expect these narratives. We should also expect that what we won’t be hearing much of is the other side of the story. The side that doesn’t reward the players in the system when it’s told or as it plays out. It’s on us as investors and individuals within the system to understand that dynamic and seek out the less profitable arguments. Our clients pay us to grow and protect their wealth and our sole source of revenue comes from them – we’ve made a conscious decision to keep other interested parties from renting control of our brainwaves. Thinking critically about events like the Japan bubble, and appreciating that the people operating up to and throughout that experience were no less intelligent and well-intentioned than we are now, is crucial. Expecting that we are somehow immune to a similar outcome is naïve. Seeing and acknowledging risks like these, and fighting hard to resist the strong human impulse to ignore them, gives us an opportunity to be more resilient when things get hard. As we’ve written plenty about, avoiding bubble risk doesn’t have to mean we stop investing. Quite the contrary. It actually means we stop speculating and start investing – something most still overly exposed to traditional stocks haven’t yet done.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the February 2025 edition of our Cadence Clips newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.