We humans aren’t great at evaluating risk. Take the person who habitually texts while driving. We all know that’s a risk, but we have a way of rationalizing behavior like that. Texting on a country road doesn’t carry the risk of texting in front of a school, and texting while driving alone doesn’t carry the risk of texting with children in the car, for example. Our brains find ways to give us permission, and I’m sure the person texting with kids in the car WHILE driving through a school zone also finds a way to give themselves the permission to run that elevated level of risk.

We tend to evaluate risk based on emotion and experience as opposed to logic and reason. Because nothing bad has ever happened while we’ve been texting and driving, we begin to overestimate our abilities and underestimate the risks involved. The people crashing while texting must be worse at it than we are. What were they even thinking? The fact that they’ve crashed and we haven’t means, at least to us, that the risk of our doing it is much lower than theirs. But there’s nothing true in that, of course. The risk someone runs while texting and driving the 100th time is the same as the 1st time. In fact, the risk might even be higher as they may now have a false sense of security brought on by the 99 times they texted and didn’t crash, so are now even less careful.

When it comes to financial risk, we are frequently just as illogical. For some reason, we see less risk in buying stocks that have already appreciated a lot than in buying those that have gone on sale. When it comes to sweaters, we’re happy shopping the sale; when it comes to stocks, we are less comfortable. With individual stocks that can make sense in some cases, as when a company’s stock is decreasing in price because the company itself is struggling, there is real risk the company could fail and the investment falls to $0. However, with a diversified mutual fund or exchange-traded fund, the risk of the share price going to $0 is nearly non-existent.

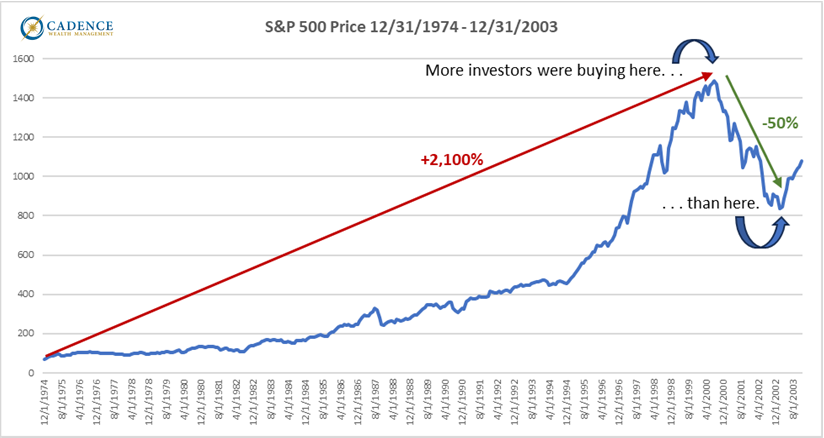

Consider the price moves of the S&P 500 index in early 2000 as the internet bubble was bursting. Between 1996 and 2013, which are the years covered by the data I sourced, more funds were flowing into the S&P 500 index around the time the index was peaking than at any other time in that span. Investors were pouring money into an index that had been almost only going up for over 26 years. At that peak, the price of the S&P 500 had increased over 2,100% since its December 1974 lows. Anyone buying the S&P 500 at that point would not see a positive price return for 13 years. Meanwhile, when the S&P 500’s price was bottoming out for good in early March 2003 after losing nearly -50% of its value, many more people were still selling stocks than buying them.

In other words, to the human brain, buying after a price increase of 2,100% is much more attractive than buying after a price decrease of -50%. Would you go out and buy a sweater that had a price mark-up of 2,100% over one that had a price reduction of -50%? Well, sure, how ugly are the sweaters, but in this case IT’S THE SAME SWEATER.

And here we’ve reached that false sense of security again, like texting while driving for the 100th time. If an equity investment is getting more expensive, it must be safe; if an equity investment is getting less expensive, it must be risky, or so we feel. Of course, it is frequently the opposite, especially long into a bull market. Frankly, and obviously, much of the risk is out of a diversified investment once its price has declined -50%. There is risk in NOT investing in growth-oriented assets to be sure, but overriding the complacency that comes with a long bull market to lighten up on equities and reduce your risk, and overriding the emotion that comes with a major stock market crash to increase your equity holdings at an opportune time is a proper way of evaluating and acting on equity investment risk.

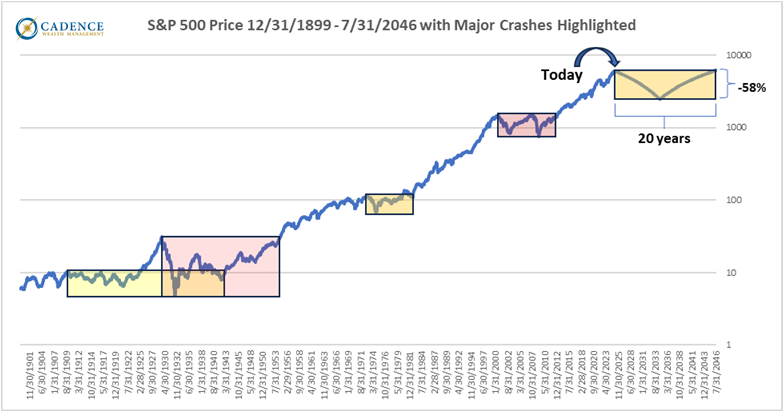

Where does the market go from where it is today? Over the short term, no one knows, but we have not seen the last of the major crashes, and we are once again in a position where US stocks are historically expensive by many measures. If the S&P 500 index were to peak now, lose the average amount of value of the last four major crashes since 1899, and take as long to fall and rise back to where it started as those crashes, it would lose -58% and take 20 years to grow back:

If a 20 year sideways move for the US stock market seems improbable, know that it has happened before, and that foreign stocks just recently completed a 22 1/2 year sideways move a few years ago. If foreign stocks fall -33% from where they are today, then that sideways move gets extended past 25 years. It does happen, it can happen, and it will happen again.

If there is any silver lining in buying after a 2,100% increase and then selling after a -50% decrease, were someone to time it perfectly wrong, then at least there is 50% of the investment left. In the case of the risks we carry in terms of dying prematurely, becoming too disabled to work, or needing skilled nursing care at some point in the future, there is no real silver lining. Ignoring those particular risks completely until something happens and then trying to shift some of the financial risk to an insurer, or trying to save extra to build up higher asset reserves, means being too late. Like all forms of insurance, when you could actually use the benefits is when it is impossible to qualify for the benefits. If you want to cover those particular risks, you absolutely have to take care of it ahead of time. Life is inherently risky, which is why life, disability, long-term care, health, auto, home, fire, and flood insurance exists.

The way to combat the risks present in the US stock market, while still also owning some US stock market positions, is to diversify into the areas that are not as historically expensive, and therefore may be carrying less risk. Bonds and foreign stocks seem to be carrying less risk today than US stocks, and many precious metal and natural resource assets seem to be historically cheap relative to the US stock market. Diversifying across these other asset classes may not have delivered the eye-popping returns that having 100% of your assets in US stocks the past decade could have delivered, but they also stand a better chance of not losing as much as the US stock market were a historical crash to start tomorrow.

“Because I haven’t died yet is proof I don’t need life insurance” is about as logical as “because stocks have been going up for so long means they can’t lose a lot.” It may seem obvious when you read it, but our brains make those rationalizations constantly. Justifying any risk you take by thinking, “Because nothing bad has happened yet. . .” is both completely human and as completely foolish as thinking it can’t rain today because it didn’t yesterday. Batten down every hatch you can. Be realistic about how much you can afford to lose, and what the financial effects of something happening to you physically would mean to you and those dependent on you. Those risks can all be addressed. We know, because we help clients do it every day. Bad financial outcomes happen to everyone at some point. Do not underestimate the financial risks present in every day life, especially when you can do something about them before it is too late.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the August 2025 edition of our Cadence Clips newsletter.

Important Disclosures

This blog is provided for informational purposes and is not to be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Cadence Wealth Management, LLC, a registered investment advisor, may only provide advice after entering into an advisory agreement and obtaining all relevant information from a client. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect charges and expenses and is not based on actual advisory client assets. Index performance does include the reinvestment of dividends and other distributions

The views expressed in the referenced materials are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur. Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.