Life is complicated, but does passing money to your beneficiaries have to be also? In theory it shouldn’t, as all you want to specify is “when I die, give this much to these people”. That sounds so simple, yet when it comes time to create a process that would allow that to happen, a lot of picky little details get in the way. Getting any of them wrong increases the chances that your estate plans could go awry.

Consider these eight ways to get your estate strategy correct:

1) The More Accounts and Institutions, the More Paperwork.

Every account you own will need to pass to someone after your death. The more different financial institutions with which you have relationships, the more work your executor will have to do. Additionally, every asset beneficiary (as opposed to insurance beneficiary) will need to open accounts at each relevant financial institution after your death before those assets can pass to them, even if they are ultimately not going to keep the money in those new accounts. Each financial institution has its own set of policies and procedures when it comes to passing inherited accounts, requiring different hoops through which to jump, like needing things to be notarized or medallion stamped.

To make it easier on the executor of your estate as well as on your beneficiaries, consider consolidating accounts and institutions. Don’t let those old stock certificates gather dust in a drawer – get them inside an account. If you ever bought shares directly from a company and a third party like Computershare keeps those records, consider transferring those investments to existing accounts as well. Quite frequently estates don’t pass to beneficiaries as quickly, cheaply, or completely because the executor or executrix, as well as the beneficiaries, just have too much to do to get everything transferred properly. Minimizing the number of accounts and different institutions involved will save someone a lot of work down the road, minimizing time and mistakes.

2) Unlimited Marital Deductions Do Not Work for Non-Citizen Spouses.

For state and federal estate tax purposes, deceased spouses can pass an unlimited amount to their surviving spouses, but not if the surviving spouse isn’t a US Citizen. Surviving non-citizen spouses can still inherit a tax-free estate amount up to the federal exemption, which this year (2017) is $5.49M. In addition, a spouse can gift up to $149,000 in 2017 to a non-citizen spouse, which is indexed for inflation each following year on top of the $5.49M exemption amount.

However, state exemption amounts are much lower and as a result a non-citizen spouse may pay a fair amount in state estate taxes that a citizen spouse wouldn’t. In Rhode Island, the state estate tax kicks in for amounts above $1.5M, and in Massachusetts that exemption amount is only $1M. We say “only” because between assets, insurance policies and home values, it is not difficult for one’s estate to be worth more than $1M. Were a Massachusetts spouse with a $1.5M estate to die and pass that to a non-citizen spouse, it would result in an approximate $70,000 state estate tax bill. Being a non-citizen just got expensive!

Should the deceased spouse’s estate be worth substantially more than that, not only will the estate pay an even heftier state estate tax bill, it might also have to pay a federal estate tax bill, the rate of which is much, much higher than for individual states. To pass an estate worth $6.49M to a non-citizen spouse in Massachusetts, the estate would pay approximately $823,000 in state estate taxes and $360,000 in federal estate taxes. $1.2M is a big, BIG bite to take from a non-citizens spouse where a citizen spouse would receive it all estate tax free.

What are the solutions? One is to open a “qualified domestic trust” before the citizen spouse dies and get it sorted that way, or another is the non-citizen spouse can become a citizen and save a lot of time, paperwork, and potentially quite a bit of money.

3) You Can Accidentally Leave Your Spouse Destitute.

Ok, that was dramatic. Maybe “destitute” isn’t the correct word, but because the static language in a trust can lose its effectiveness over the years as tax and estate laws change, it is possible for the wording in a trust to not work as intended years in the future. Consider this: years ago when the federal estate tax exemption amount was much lower, it was common for spouses to leave an “amount up to the federal exemption amount” into one trust, and then leave the remainder to the surviving spouse. By putting an amount equal to the federal estate exemption amount into a trust, this maximized the estate exemption and reduced the estate taxes on the second death as much as possible. When someone died with a $2M estate, $1M would go into a trust and $1M would go to the surviving spouse, with no estate taxes being paid. That $1M in the trust would be forever safe from estate taxes, such that when the surviving spouse finally died with his or her own $2M estate, only $1M of the total would be taxed. Had the first spouse left everything to his or her spouse instead, the full $3M would be owned by the surviving spouse, and upon his or her death $2M would be taxed. At a tax rate of approximately 40%, that strategy saved a cool $400,000 in federal estate taxes alone, plus potential state estate taxes.

However, that exemption amount has continued increasing over the years. It is now high enough where that same estate structure designed to minimize estate taxes might now pass nothing directly to a surviving spouse. If that same person mentioned earlier died with his or her $2M estate and the trust language still said to put an amount “up to the federal exemption amount” into a trust, then all $2M would go into that trust and none would go directly to his or her spouse. If there is a large imbalance between what is owned by one spouse versus another, a strategy like this, which worked perfectly well 15 years ago, may now leave the surviving spouse little beyond being able to live off the income from a trust from which he or she has a limited ability to withdraw principal.

And this is just one example of how old trust language may no longer work well with current federal and state exemption amounts. Just because you created a trust years ago does not mean that trust will function exactly as you’d originally intended once it does finally get used. Make sure you review it, and the longer ago you created it, the sooner you should.

4) Primary vs Contingent vs Other Beneficiary Categories.

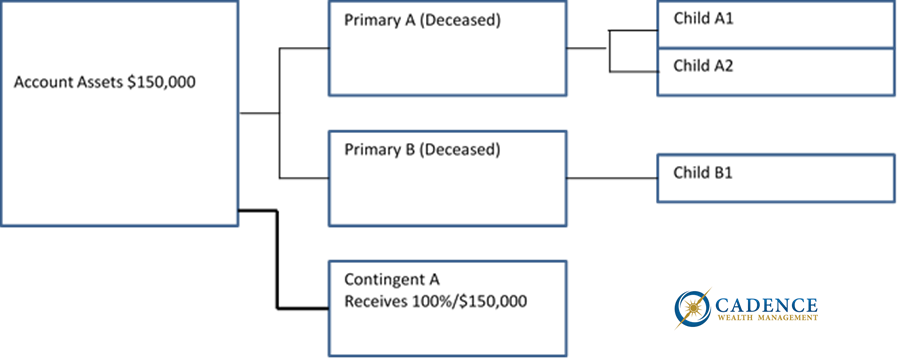

When you fill out beneficiary forms for bank and investment accounts or insurance policies, there are usually two classes of beneficiaries: Primary and Contingent. In that set-up, the ONLY way the contingent beneficiaries receive any inheritance is if all primary beneficiaries predecease the account holder or the insured. One problem with that set-up is that you could inadvertently disinherit your grandchildren, because if you miss what is sometimes just a little check-box in the beneficiary forms, you might end up with this:

The children of both deceased primary beneficiaries should have received their parents’ shares, at least that’s what you wanted. Instead, they were skipped over and your sole contingent beneficiary ended up with all the money.

Naming your two children as your primary beneficiaries and your three grandchildren as contingent beneficiaries, for instance, will not fully solve this problem either, as the only way your grandchildren will receive any of the inherited funds is if BOTH of your children predecease you. If one of your children is alive at your death, all the money would go to that one surviving child if you had your grandchildren as contingent beneficiaries and they would still not receive anything.

The way around that is to look for a check-box on the beneficiary form that talks about “per stirpes or per capita” distributions, or something called the “grandparent clause”. What this check box allows you to specify is that should a primary beneficiary predecease you, then his or her share would go to his or her children as opposed to 100% of the inheritance going to the other surviving primary beneficiaries. This is EXTREMELY important, as many people miss this checkbox and unintentionally disinherit their grandchildren.

If your primary beneficiaries already have or might have children some day, especially if the primaries are your own children, do not rely on the “contingent beneficiary” designations to take care of getting the money to your grandchildren. Look for the “per stirpes”, “per capita”, “grandparents clause” language, or anything that allows you to specify in the event of any of your primary beneficiaries predeceasing you, his or her share should go to his or her children.

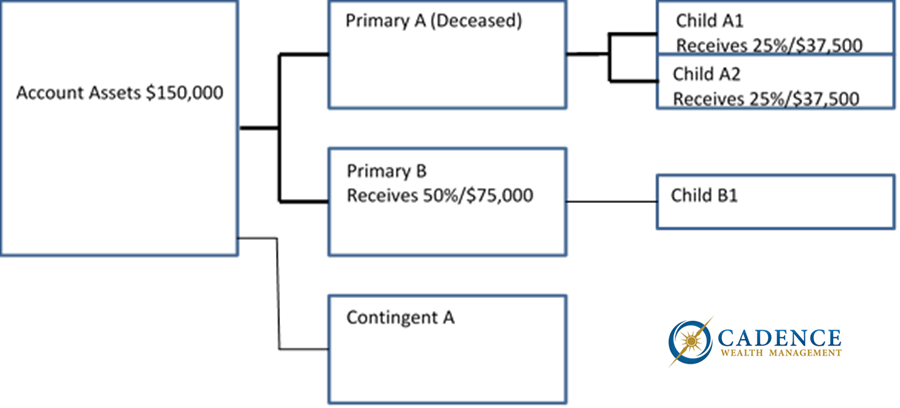

The difference between “per stirpes” and “per capita” only factors in when all your primary beneficiaries predecease you. A “per stirpes” designation means each primary beneficiary’s share will be divided equally between his or her children, whereas a “per capita” designation means all the children of the primary beneficiaries will split the inheritance equally.

In the case above, in the event both primary beneficiaries predecease you, a per stirpes designation would see the two children of the first primary beneficiary split 50% equally between them, so 25% each, and the one child of the other primary beneficiary would keep the full 50% originally intended for his or her parent. If you wanted all grandchildren to receive equal amounts, in this case dividing the pot between the 3 of them, select the “per capita” designation and they will each get 33.3%.

In the end, contingent beneficiary designations should be considered for people who are not the children of your primary beneficiaries.

5) Minor Beneficiaries.

The treatment of minors inheriting assets is slightly different between investment accounts and insurance, but ultimately relies upon the trustworthiness of their named or appointed guardian. In the case of investment accounts, if one or more minors inherit them, new accounts are opened in the minors’ names with their designated guardian given control over the accounts. The minors will not have any control over those accounts until they reach the age of majority, which in financial terms is 18, not to be confused with minor designations for purchasing alcohol, for example.

If that seems like the minors’ designated guardian has a lot of control over financial assets that were supposed to be set aside for the beneficiaries themselves, then hold onto your hat because insurance proceeds are, without additional structures in place, generally paid out DIRECTLY to the designated guardian. The check is cut in his or her name.

In the event you are concerned your minor beneficiaries’ guardians are good at raising children but bad at managing money, you may want to create a trust to hold the money for the beneficiaries that will allow you to at least define how money can be spent on behalf of your minor beneficiaries. That can still provide quite a bit of latitude for a designated guardian if she or he is the trustee of the trust, so appointing someone other than the minor’s designated beneficiary as trustee of that trust to make the financial decisions would provide more financial restrictions and control over those assets on behalf of your minor beneficiaries.

6) Having Trusts as IRA Beneficiaries.

Having a trust as the beneficiary of an IRA or other retirement assets is a nice way to accommodate situations that normal beneficiary forms cannot handle, like complicated beneficiary splits, or a much more impactful concept: forcing your beneficiaries to “stretch” the IRA’s assets. Because most inherited IRAs are drained by their beneficiaries within just a few years, the favorable IRA tax treatment gets lost. By having a “retirement income trust” as the beneficiary of your IRA assets, and by appointing a trustee other than the trust’s beneficiaries to make distribution decisions from those IRAs, it guarantees your beneficiaries will not be raiding those accounts, losing much to income taxes. Instead of allowing them unhindered access to those assets, the retirement income trust only allows your beneficiaries to take smaller annual distributions from the trust, a process known as “stretching”. With the proper trust, this arrangement can even extend all the way to the children of your beneficiaries one day becoming the income beneficiaries of the trust.

If you are not worried about your beneficiaries prematurely draining these assets, there is one thing to make sure of if you have a regular, non-retirement income trust as your IRA beneficiary. For the trust beneficiaries to still be able to “stretch” these assets, every beneficiary of the trust must be an actual human being. Even if you leave 99% of the inherited trust assets to people and that final 1% to a charity, the trust would lose its ability to offer on-going favorable tax treatment, “stretching”, to the human beneficiaries. They would need to remove those funds from the retirement accounts within a relatively short period of time and pay income taxes on them. That’s a lot of money that gets lost to taxes because 1% was left to a charity. Perhaps naming the charity as the beneficiary on one of the accounts or on an insurance policy instead of the trust would be a better solution.

7) Trusts Have to Get Funded to Work.

You might be surprised how often we see this. Clients come in with trust paperwork only to realize they created the trusts but aren’t actually using them because the trusts neither own anything, nor are the beneficiary of anything, nor does any other document, like a will, state how those trusts will be funded upon death. Just opening a trust doesn’t do anything; you have to take the next step and transfer the ownership of accounts into the name of the trust, or modify beneficiary paperwork or your will to name the trust as a primary or contingent beneficiary. Failure to do that results in rather expensive but completely useless trust paperwork. If you have perfectly good trusts, make sure they either own or are the beneficiary of something.

8) Few Paths in Life Are Straight Forever.

We will close with this: life has a funny way of proving you wrong. As a result, the people to whom you initially want to leave your money can change over time. Think of the young employee that leaves her 401(k) to her parents in the event of her death and forgets to change that after she marries and has kids. Guess who inherits that account should she die?

Or consider husbands and wives who divorce and remarry but neglect to change their insurance beneficiaries. Won’t their second spouses be surprised?

Or consider the grandparents who name their first three grandchildren by name as their beneficiaries, only to have one new grandchild long enough after those accounts were designated that the final name never gets added.

Or. . .

You understand the point. Most people’s paths wind through life more than they’d anticipated, and it is quite easy for little details to fade with time only to reappear later in life when the desired beneficiaries have changed but now it’s too late to change the paperwork. Stay on top of whom you’ve named as your beneficiaries. Check the beneficiary designations if you haven’t in a while, and make it a habit of either continuing to check them, or at the very least remembering them with every life change. We do not have enough paper to tell you the stories we’ve seen first-hand of one missed checkbox diverting substantial sums from a desired beneficiary to a less desired one.

As easy as “leave this amount to these people” should be, life, paperwork, time, changing IRS guidelines and estate laws are all hurdles that have to be overcome to make sure the proper people and/or organizations receive what you would want after you die. You worked hard to earn and save it, so use these eight ideas and your Cadence Wealth advisor to make sure it will go to where you want it.